Tonight’s post, as the title indicates, is about Pacing Strategy, and specifically, does a negative split improve performance? Part of my Dorset Trail Marathon race report last week included a bit of a ‘rant’ about how I felt that the negative split resulted in slower finishing times, not quicker as suggested by many, including Martin and Tom from MarathonTalk. Well following my post it was pleasing to know that both Martin and Tom read my race report with them both leaving a comment on the blog. I especially liked Tom’s quote "I'd rather know I was wrong than think I was right". So it got me questioning what is it that makes me think that I am right, that makes me believe that the negative split is the wrong strategy? So hopefully tonight I will provide some material to confirm my beliefs, but I guess the real purpose, as with most of my blog posts, is to encourage you the reader, to question your approach to running, to consider alternative approaches, even if they are not in agreement with the accepted norm, and at first impressions appear a ‘bit too far out of the box’!

The starting point is first to confirm what causes fatigue during endurance running performance. As mentioned in previous posts, fatigue in the past used to be considered to be due to peripheral fatigue, for marathons, typically due to glycogen/carbohydrate depletion. With the availability of carbohydrate gels, fatigue in marathons now seldom occurs due to low blood glucose levels, as evidenced by the frequent sight from the 1980s of jelly legged runners stumbling towards the finish line of the London Marathon, now a very rare occurrence. The latest research, initiated by Professor Tim Noakes, highlights the importance of the brain (The Central Governor) and more specifically the integral role of RPE (Rating of Perceived Exertion). While doing physical activity, the runner rates their perception of exertion, i.e. their feeling of how heavy and strenuous the exercise feels, combining all sensations and feelings of physical stress, effort, and fatigue. This rating, typically known as the Borg Scale 6-20, (as there is also an alternative 1 – 10 scale) ranges from 6 (no exertion at all) up to 20 (maximal exertion), has been shown within the scientific research to be a stronger predictor of fatigue than any physiological measurements. The latest fatigue models within the scientific literature therefore propose that fatigue within endurance events occur once a maximal RPE is reached. Therefore during the marathon one should have a strategy that prevents one’s RPE from reaching maximum levels prior to the finish line.

Although I accept that RPE is the core component that contributes to fatigue during endurance events, the concept that maximal RPE must occur in order for fatigue to take place, in my experiences doesn’t seem to ‘fit’. During the latter stages of ultra races and marathons, I am not really working at a very high intensity, so I am therefore not experiencing maximal levels of physical stress, although there are high levels of effort, although this is what would typically be classified as mental effort. If one takes on board a ‘fuller/wider’ interpretation of RPE, more than the physical stress/fatigue, then I suppose the maximal RPE concept contributing to fatigue can apply. However, I prefer the introduction of a new theoretical measure known as RFE (Race Focus Energy). Where RFE is a measure of the mental effort, the concentration, the race focus required in order to keep running at a fast pace, i.e. a race pace. RFE is largely determined by RPE, however, the relationship between the two is not directly linked, with many aspects, specifically positivity and negativity, being able to alter the link between the two, i.e. swing the arrow up or down. The RFE Fatigue model also ‘fits in nicely’ with most marathon runner’s experiences, i.e. that towards the end of the race, they run out of energy. Remember, this is no longer carbohydrate / biochemical energy, but more likely Race Focus Energy, or simply mental energy.

Therefore to improve performance during an endurance event such as a marathon, one either has to ensure RPE doesn’t reach maximal levels, or alternatively adopting the RFE Fatigue Model, ensure one does not empty their RFE tank prior to the finish line. At first I will disregard the impact of positivity/negativity and simply look at RFE as being directly determined by RPE. Then if I aren’t too fatigued I will attempt to introduce where positivity and negativity fits in.

The key idea behind an equal paced marathon running strategy is for the “power output” as Tom describes it, to remain even throughout the entire race. With even power output on a flat course translating to even running pace, i.e. constant minute per mile rate, and subsequently equal half marathon split times. The only problem with this idea is that an even pace throughout a marathon does not mean you are running at an even physiological intensity. Due to a number of physiological aspects that occur as the duration of the race increases, such as dehydration, muscles gradually fatiguing, and possible changes in fuel utilisation towards an increase in fat burning (which requires more oxygen for the same ATP generation), there is an increase in the physiological load for the same power output / running pace, which is known as cardiac drift. Runners will be well aware of this if they race with a heart rate monitor, as they will observe a gradual increase in heart rate throughout the race, with the increase being greater during the latter stages of the race, even if they maintain a constant running pace.

Runners who don’t use a heart rate monitor will also be well aware of this phenomenon when reflecting on how ‘hard’ the race was, as their Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE) increases as the duration of the race progresses when running at a constant pace. Typically, if adopting a constant pace strategy, their RPE would be low at the start of the race, maybe around 11(Light) – 13 (Somewhat Hard), and then progressively increases up towards 17(Very Hard) – 19 (Extremely Hard) during the latter stages of the race. An increase in RPE therefore results in an increased usage rate of RFE. The figure below is taken from Parry et al., 2011. An article on perceived exertion among Ironman triathletes, within November's edition of BJSM. The figure clearly shows how the RPE increases during the marathon (of an Ironman), even though the actual running pace decreases as the marathon progresses. (The decrease in running speed is not clearly illustrated by the poor scale on the axis, up to 30 km/hr!) It looks like the pace has dropped from around 10.1 km/hr (5:56 per km) down to around 8.8 km/hr (6:49 per km). Therefore to maintain an even running pace throughout the entire marathon would require an even larger rise in RPE than illustrated within the figure below.

I guess the ‘million dollar’ question is, “Is this progressive increase in intensity, from light at the start, up to hard at the end, really the best pacing strategy?” If we look at the strategy to reduce the likelihood of emptying one’s RFE tank, then one would conclude that starting at an easy pace, where the RFE usage is low at the start, would lessen the chance of running out of RFE before the end of the race. However, due to running at a lower intensity, this means you are actually running slower than what you could have run at. The theory behind the even power output is that because you have taken the first half easy, i.e. with minimal Race Focus Energy, then you are more likely to be able to maintain the same running pace during the second half of the race, as your RFE tank will be substantially fuller than if you had started with a higher intensity, at a higher usage of RFE.

The even power output strategy therefore looks good. However, what happens during the second half of the race? Remember an even power output strategy (even running pace on a flat course) means you have run at a slower pace than you could have achieved, so you have time to make up in order to cross the finish line in a quicker time. What it gets down to is how much extra RFE will you consume during the second half of the race in order to maintain the same running pace, over and above the amount you would have consumed, if you had started running initially at a higher intensity, therefore at a quicker running pace, and therefore having the ‘luxury’ of being able to reduce your pace during the second half, and hence use less RFE? As just highlighted, the benefit of starting at a quicker pace is that you are able to keep the RFE usage, (or the RPE value), the same during the second half of the race, as you have ‘time up your sleeve’ so therefore able to allow the pace to drop gradually to equally match the gradual increase in physiological load as a result of cardiac drift.

The confusion often arises because it is assumed that starting at a quicker pace, i.e. quicker than what you are capable of maintaining for the entire duration of the race, means that you are working at a higher physiological intensity, higher than what you could maintain for the entire duration of the race. This assumption is incorrect. By starting at a quicker pace, you are actually keeping the physiological loading, the intensity, the RPE, and most importantly the RFE at a more even value! It is attempting to run at an even pace, with an even power output, that results in large variations in physiological loading, RPE and RFE. It is typically assumed for most variables that an even constant value is more efficient than fluctuations or a wide range of values. So YES adopting an even strategy is the answer, but not an even running pace, or an even power output strategy, but a strategy that results in an even physiological intensity, and an even usage of Race Focus Energy!,

Looking at the example of a runner adopting an even power output strategy, means the runner has taken it easy at the start, running slower than one could quite easily have run at, as there is no fatigue, heart rate is therefore the lowest it will be throughout the entire race before cardiac drift, and their RPE will also be at the lowest, as this continuously rises during the race, as clearly illustrate in the figure above. However, will they actually be able to translate having a fuller tank of RFE leading into the second half of the race into actually maintaining the same even running pace? Before answering this question, there is one aspect that I haven’t mentioned yet: muscle fatigue / muscle damage. The muscular force required from your lower limbs to run is typically in the region of around 20% of one’s maximal force value that they can generate. Now during endurance running, as muscles gradually fatigue, the decline in the muscle force that is able to be generated actually plateaus, at a level of around 30 - 40% decrease. So even at the end of ultra races, the muscles are still able to generate 60 - 70% of their maximal force, which you can see is significantly more than the 20% that is needed to run. So the muscle fatiguing aren’t actually the limiting factor. They simply cause the running to be less efficient, hence the drift upwards in heart rate, RPE and therefore increased RFE usage, at the same running pace.

The problem during marathon / ultra running is actually the muscle damage, the increased pain the runner feels as the race progresses, on each and every foot strike. This pain is usually worse on the down hills where the muscles are contracting eccentrically (i.e. the muscle lengthens as it contracts) and also during road racing, where there isn’t the same ‘give’ in the road as there is on the trails. So during the latter periods of endurance races, such as a marathon, although the runner that started at an easy pace has more RFE in the tank, the usage rate is now magnified immensely simply due to the pain from the muscle damage. If you reflect back to your last marathon or ultra race, how much mental focus did it take to keep moving at a reasonable pace when your legs were ‘screaming’ for you to stop? There was most likely increased RFE usage simply due to the muscle damage pain! Yes, if your experiences were similar to my typical experience in an ultra race, then it probably took significantly higher levels of RFE to maintain the same pace. Not due to a lack of physiological fitness such as VO2 max, or lactate threshold, but simply due to the muscle damage that is unavoidable in endurance racing. One could suggest that the muscle damage would be more if the runner runs the first half of the race at a faster pace, however, the muscle damage is much more time/duration dependent rather than pace dependent, especially when running on the trails, where the running pace effect on muscle damage is even much smaller. It isn’t just muscle damage that can cause the RFE usage to significantly increase during the latter stages of the race. Other factors such as blisters, cramps, dehydration, overheating, stomach/digestion issues etc, can all increase significantly the amount of Race Focus Energy that is required in order to maintain the same running pace.

Hopefully it is becoming clearer in terms of ‘where I am coming from’! Slowing down during the second half of a marathon isn’t solely determined by the pace the runner runs the first half in. Yes, it does play a part, as a quicker pace will have used up more RFE, but during the second half of the race, there are so many other factors that can significantly increase the RFE usage rate, which far exceeds any ‘savings’ achieved by running at an easy pace during the first half. Those runners that are able to maintain an even paced marathon, or even a negative split, in some ways are achieving it, perhaps one could say by as much a little bit of luck, as opposed to their physical preparation (which plays an important role – but another post), or more specific to this post, as opposed to their conservative running pace in the first half. The easy running pace during the first half I believe plays only a little part in everything seeming to ‘fall into place’, i.e. that they didn’t cramp, didn’t get dehydrated, didn’t get blisters, didn’t get overly painful muscle damage etc., and with the easy running pace during the first half I would suggest most likely does not have such a large affect, that it was worth ‘wasting’ the opportunity to run faster while they could, before these multitude of potential problems possibly arise during the second half. Hence my philosophy; “Run as fast as you can, WHILE you can!” Before the muscle damage, dehydration, etc. massively increases the rate of RFE usage!

Although I haven’t even touched on the role of positivity and negativity above, (another post), now is a good time to look at some actual race data. Is this ability to run an even running pace in a marathon, or even better, to run a negative split, actually an indication of a good performance, of being a better runner? Is it a quality of better runners, such as one may associate a high VO2 max or lactate threshold as a quality of better runners? And secondly, how many runners actually achieve this so called ‘great running performance’ to achieve a negative split. If you achieved it, would you therefore be within the ‘quality’ runners that make up say 10% of all runners, or is this quality performance not that distinctive, and in fact you are just one of say 20% of all runners. Still an aspiration to aspire to, to be within the ‘best’ 20% of the field, as remember, the negative split is portrayed as THE achievement!

To help answer these questions I looked at the results from this year’s Virgin London Marathon. Perhaps as one would expect, based on the status the negative split has, both the male and female winners ran negative splits. So therefore why have I wasted all of this time typing up this blog post, attempting to get you to consider that the negative split isn’t what it is made out to be? But let’s look a little deeper at the results. How many of the other 99 runners in the top 100 in the massed start race also achieved a negative split? Remember these runners are the very best, at the very front of a field of over 35,000 finishers. Surely then one would expect around half of the top 100, or at least a third! No, only seven other runners in the top 100 finishers ran a negative split. This ‘strange’ result could however be because at the front of the race many of the runners went out with the pace makers at nearly world record pace, in the hope of hanging in there to the finish, they therefore were never going to achieve a negative split. So if I look at how many within the next 100 places from 101 – 200 achieved a negative split, this would give perhaps a more true representation of the frequency of the negative split occurring. These runners from 101 – 200 are still top quality runners, and in relation to the overall field, very, very fast runners, with an average finish time of 2 hours 39 minutes. The results show that there were only 6 negative split runners from the 100.

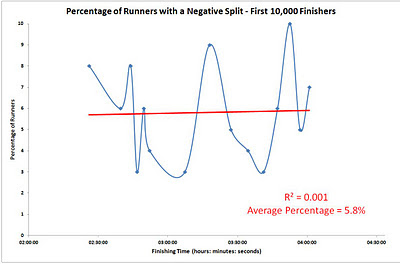

If you look at the following graph, that shows the number of runners that negative split from samples of 100 runners at different time gaps for the first 10,000 finishers, then you will see that there is ABSOLUTELY no relationship at all between the finish time of the runners and the percentage that achieve a negative split. If running a negative split was a quality of being a good runner, of a good performance, then surely one would expect that further towards the front of the field there would be a higher percentage? With a correlation of pretty well zero, one shouldn’t need any more evidence that the negative split is NOT something to aim for, NOT something that indicates that you performed well!

Another key statistic is the percentage of runners within the first 10,000 finishers that actually achieve it, being only 5.8%. With this evidence it therefore still amazes me that there seems to be the message ‘out there’ that the negative split is something all runners should aim for. If we look at a 10% sample, in batches of 100 runners, spread throughout the 23,600 runners that finished within 5 hours at London, then the percentage that achieve a negative split drops even lower to only 4.3% of finishers! The following graph also show how the positive split slowing down time increases as the finishing time increases.

A really issue that needs attention is in terms of the potential effect this low percentage of negative splits may have on the marathon finishers, when 95.7% of them do not achieve probably the number one goal that is drummed into them apart from finishing! Remember the message ‘out there’ that the negative split indicates that you ran well, probably even more important than your actual finishing time. So 95.7% of runners are potentially disappointed because they didn’t achieve one of their goals. So if they do another marathon, which hopefully they will still want to, even after the disappointment of not negative splitting, then what do you think their likely race strategy will be for their next marathon? Well I would suspect that they would likely run the first half of the next marathon at an even slower, easier pace, as they possibly would have concluded that the reason that they didn’t achieve the negative split is that they started off too fast, and therefore that is why they ran out of energy. Which they may associate as running out of carbohydrate energy, as it is reasonably well known within the running community that the higher the physiological intensity, the greater the usage of carbohydrate. But remember that is the old model of endurance fatigue, before gels were available. Carbohydrate depletion is no longer the cause of fatigue in marathon runners.

As I have mentioned above, fatigue is more likely a consequence of RPE, or specifically getting close to emptying the tank of Race Focus Energy. As many runners are not aware of the latest fatigue research which is based on the Central Governor, i.e. the brain, it is probable that most runners are likely to conclude that their running pace being too fast at the start was probably the cause of their fatigue! And as I have highlighted above, the rate of RFE usage during the second half of a marathon is determined by much, much more than one’s running pace during the first half of the race. So starting their subsequent marathon at an even slower running pace, doesn’t guarantee that they will achieve this much wanted negative split goal, as demonstrated by only 4.3% of runners finishing in less than 5 hours achieving it.

Well, time to take a breathe! Phew, I think I have definitely got this negative split ‘dislike’ off my chest!

I think now is an appropriate time to call it a night. Hopefully those of you that have reached this far, have found something worthwhile within this blog, once you manage to navigate past the occasional frustration that may be evident within my writing. Please feel free to leave me a comment, explaining where I have gone astray, where I have got it wrong. I’m not saying that my ideas must be right, probably on most occasions, the majority of you would conclude that my ideas are a bit ‘far-fetched’, however, with regards to pacing strategy, hopefully I have at least got you questioning that maybe it is the negative split concept that this time is too ‘far-fetched’!

I will sign off with a quote from Tom Williams from MarathonTalk, which was within the comment he left on last week’s race report post:

“A large amount of what we achieve is governed by our mental state and how we see ourselves. (It is) a lot about opening the mind to what might be possible when we throw away the self imposed limitations of our mind.” Tom Williams, 2011.All the best with the formulation of your pacing strategy for your next race. Remember, whatever strategy you adopt, you must have total belief that it is the right strategy that works for you.

Stuart

Interesting read. First a disclaimer - I am not a doctor, and much of what I am going to say is from reading other studies and my own intuition (which could be completely worthless).

ReplyDeleteI agree with some parts, and disagree with other parts.

At any given distance, I believe each individual has their own pace that will provide a most consistent effort. Even at extreme distances like 100 miles, I argue that the more constant you can keep your pacing, the closer you will be to your best possible time. Can't run 11 minute miles for 100 miles? Then run 8 minute miles and walk for a bit every 5 minutes.

There are numerous studies I have read which show that a great many victories and records in running (nearly all) come during even to slightly negative pacing.

1) http://sweatscience.com/pacing-and-cognitive-development

2) http://running.competitor.com/2010/11/training/the-art-and-science-of-marathon-pacing_16984

I'm sure you can Google plenty of others.

No offense to hundreds of thousands of runners, but quite frankly I don't care that 95% of them run positive splits. The real question should be could they have run a faster time if they would have run more even splits? And again, who cares if it was even a PR - could that PR have been a better PR?

I think this topic is very hard scientifically to prove physiologically...but I do think a big stack of correlated data is useful. If you look at the data and nearly all world records at all distances come from even to slightly negative splits, that has to mean something. Random middle of the pack people running positive splits to me only solidifies the point.

http://sweatscience.com/mental-effort-increases-physical-fatigue-reduces-hr-variability

On the mental side, I think you will also get a positive benefit from such pacing as well. How many times have you read that when people start positive splitting and slowing down they lost all motivation and shut 'er down?

Thanks for another thought provoking post. I, too, believe that a positive split could be better for a marathon, not to mention the ultras. But how much of a positive split is best, that I can't figure out.

ReplyDeleteIf you were to run a road marathon next week, what would be your estimated splits for both halves? How fast would you run the first half? As if you were running a half marathon? Similarly, how fast would you run the first 10K?

Hey Stu,

ReplyDeleteJust wanted to thank you for all the interesting posts. Are you doing any talks at this year Lakeland recce's?

Hi Brett, Starks, Simon

ReplyDeleteThanks for the comments, and Starks apologies for the delay in responding to your question. See my blog post later tonight.

With regards to doing a talk at this year's Lakeland recces. Unfortunately I am unable to make it to any of the recce weekends this year as I will be in New Zealand or racing down south. But if you live down south, I have a talk coming up on the 17th Feb. (see tonight's post).

Stuart

Stuart,

DeleteSeems to me that the negative split advice handed down over the years needs to be questioned by most if not all marathon runners. Regardless of standard: beginner-elite, very few runners manage it.

I came across this excellent post when I was writing about the perils of negative split marathon pacing. Chasing what I called the 'fool's goal' only increases the tremendous mental burden inherent in latter stages of a marathon.

BTW, Sorry to read about your foot, hope it is mending.

Graham

How much negative and how much positive are you talking? I think everyone would agree the extreme's lead to slower times. The question is where is the "sweet spot" for each runner. For me, I've run 38 marathon over the last 20 years and my best performances come from a slight (1% negative split). If I get to close to my lactate threshold early in the race, it spells big trouble later on. You mentioned the mental aspect of exertion, yet didn't include the mental aspect of running negative splits. I just ran a 2% negative split at Erie and felt very strong the second half of the race. I was passing scores of runners and was not passed at all. I felt like a badass out there. I was hurting at mile 20, but still felt strong and picking up the pace. Several runners tried to stay with me and I knew these chumps were spent and had no chance. This fueled my competitive spirit. The last mile I kept looking for guys in my age group to hawk down. This is a VERY different mentality then when I run positive splits. I fade and struggle to minimize the fade. I'm counting the tenths of a mile and thinking OMG aren't we at mile 23 yet? How much further could it be?

ReplyDelete