Hi, and Happy New Year.

Tonight’s post will be a short post, just tying up a few issues to do with pacing during endurance events. Within my last post I focused solely on a physiological rationale for not adopting a negative split strategy, but as I have tried to explain, performance during endurance events is not determined directly by physiology but is to do with managing Race Focus Energy (RFE), so tonight’s post will hopefully provide the complete answer to the ideal pacing strategy.

One thing that has been highlighted by many, including Brett who left a comment to my last post, is that most world records, especially for track distance races, come of an even split (or a slight negative split) pacing strategy. Simply in terms of physiology I think the reason for this is that for track distance races the races are too short for cardiac drift to occur, hence an even paced strategy does correspond to an even physiological demand. But for marathons, both the men’s and women’s world records were set with a negative split. So why is this so?

Looking at my RFE fatigue model above, where physiological demand, (which could be concluded as being represented by rating of perceived exertion, RPE), is a core component. There is not a direct link from RPE to RFE. Although running a negative split could be the wrong strategy in terms of there being a progressive increase in RPE as the race progresses, the positivity one receives by not slowing down, and as you overtake other runners is likely to result in a downward swing of the RPE-RFE arrow, and therefore could result in a constant rate of RFE usage. The key here is the thoroughness of the race preparation. If you have considered the demands of the race, and prepared for a negative split (even paced) race strategy, then hopefully you have the confidence to run slowler than what you are capable of during the first half, and to not allow negativity to develop as you are further down the field than you would expect to finish. Then with the expectation that during the second half of the race you will overtake the 95.7% of the field who slow down, the positivity will hopefully counteract the increased physiological demand.

Then why is it that I don’t recommend this approach to endurance racing. I guess the main reason is that to develop this confidence to remain positive during the slowly run first half of the race is very difficult. A human trait appears to be to easily react negatively to situations whilst racing. As mentioned in my previous post, there are so many factors that can swing the RPE-RFE arrow upwards. The elite runners who adopt a negative split strategy succeed not only because of their superior physical abilities, but also due to their superior TOTAL preparation abilities. They have the ‘mental skills’, the belief, to remain positive throughout the duration of the race. Based on my experiences during 30+ years of endurance racing, I have found it extremely hard to keep the negativity ‘at bay’, hence why I adopt the positive split pacing strategy, and to quite an extreme.

My 'extreme' positive split strategy is to start at a fast pace, quicker than I am capable of maintaining for the duration of the race, i.e. “Run as fast as you can, while you can”. I am then further up the field and ahead of runners who would expect to finish ahead of me. There are two advantages of this. Firstly, if the preparation by the other runners hasn’t been thorough, then there is the likelihood that they may start to develop negative thoughts due to being behind. But the biggest advantage is the positivity I receive as a result of running fast and being up the field. I am usually on an absolute high, receiving loads of positive energy from marshals, feed station volunteers, spectators and from within. And with this positivity, although I am working at a physiologically high level, the RPE-RFE arrow is rotated down and the RFE usage is therefore lower than what would be typical for such a fast running pace. My performance at the IAU World Trail Championships in Connemara, Ireland back in July is a clear illustration of this positivity reducing the RFE usage rate, and therefore enabling me to perform so much better than what physiologically I should have been able to perform at. Starting the race fast, and actually leading the World Champs for a short period, with a helicopter buzzing above, and a camera crew on a quad bike with a camera jammed close to my face (see the video of the race on the following link: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LLUVVBUMALU) had such a massive swing of the RPE-RFE arrow, that I felt amazingly positive for the entire 7+ hours of the race, and everything felt so much easier than usual!

Again in terms of adopting a positive split strategy the key is the thoroughness of the preparation, the completeness of the visualisations. Although, it could be interpreted as being negative visualising slowing down during the second half of the race, in my situation it is a reality due to the quick pace I start at. Therefore knowing that a slowing down of pace has nothing to do with me performing poorly, this prevents the negativity from developing. Brett made a very valid point with his comment “How many times have you read that when people start positive splitting and slowing down they lost all motivation and shut 'er down?” And that is the real problem with trying to achieve a negative split, or an even paced strategy. Many runners may not be aware of cardiac drift, and that to maintain a constant pace throughout a marathon requires a massively disproportionate demand in terms of both physiological intensity and Race Focus Energy. Therefore when they are ‘required’ to slow down, yes the negativity often takes over, and then it is all ‘downhill’ from there!

So to conclude, as with most issues to do with endurance running there is not one ‘golden rule’, there is not one ‘solution to fit all’. The key to success is being aware of the different approaches and having an understanding of the underlying factors that influence performance. This is where the Race Focus Energy Fatigue Model is so beneficial, as it helps to clarify the many, many factors that contribute to race performance. It is with an increased understanding of endurance running that I look forward to another great year of running in 2012. I wish you well for the upcoming year of running, May you achieve success, by achieving the goals you set yourself. Time to sign off with a quote I have signed off before with, but I feel is quite appropriate for this post.

"In order to address what training (preparation) is appropriate, one must first consider what limits performance!" Stuart Mills, 2010.

Hope to see you at a race or two in 2012,

Stuart

Saturday, 31 December 2011

Sunday, 18 December 2011

Thoughts on Pacing Strategy for Endurance Running Races - The Negative Split

Hi

Tonight’s post, as the title indicates, is about Pacing Strategy, and specifically, does a negative split improve performance? Part of my Dorset Trail Marathon race report last week included a bit of a ‘rant’ about how I felt that the negative split resulted in slower finishing times, not quicker as suggested by many, including Martin and Tom from MarathonTalk. Well following my post it was pleasing to know that both Martin and Tom read my race report with them both leaving a comment on the blog. I especially liked Tom’s quote "I'd rather know I was wrong than think I was right". So it got me questioning what is it that makes me think that I am right, that makes me believe that the negative split is the wrong strategy? So hopefully tonight I will provide some material to confirm my beliefs, but I guess the real purpose, as with most of my blog posts, is to encourage you the reader, to question your approach to running, to consider alternative approaches, even if they are not in agreement with the accepted norm, and at first impressions appear a ‘bit too far out of the box’!

The starting point is first to confirm what causes fatigue during endurance running performance. As mentioned in previous posts, fatigue in the past used to be considered to be due to peripheral fatigue, for marathons, typically due to glycogen/carbohydrate depletion. With the availability of carbohydrate gels, fatigue in marathons now seldom occurs due to low blood glucose levels, as evidenced by the frequent sight from the 1980s of jelly legged runners stumbling towards the finish line of the London Marathon, now a very rare occurrence. The latest research, initiated by Professor Tim Noakes, highlights the importance of the brain (The Central Governor) and more specifically the integral role of RPE (Rating of Perceived Exertion). While doing physical activity, the runner rates their perception of exertion, i.e. their feeling of how heavy and strenuous the exercise feels, combining all sensations and feelings of physical stress, effort, and fatigue. This rating, typically known as the Borg Scale 6-20, (as there is also an alternative 1 – 10 scale) ranges from 6 (no exertion at all) up to 20 (maximal exertion), has been shown within the scientific research to be a stronger predictor of fatigue than any physiological measurements. The latest fatigue models within the scientific literature therefore propose that fatigue within endurance events occur once a maximal RPE is reached. Therefore during the marathon one should have a strategy that prevents one’s RPE from reaching maximum levels prior to the finish line.

Although I accept that RPE is the core component that contributes to fatigue during endurance events, the concept that maximal RPE must occur in order for fatigue to take place, in my experiences doesn’t seem to ‘fit’. During the latter stages of ultra races and marathons, I am not really working at a very high intensity, so I am therefore not experiencing maximal levels of physical stress, although there are high levels of effort, although this is what would typically be classified as mental effort. If one takes on board a ‘fuller/wider’ interpretation of RPE, more than the physical stress/fatigue, then I suppose the maximal RPE concept contributing to fatigue can apply. However, I prefer the introduction of a new theoretical measure known as RFE (Race Focus Energy). Where RFE is a measure of the mental effort, the concentration, the race focus required in order to keep running at a fast pace, i.e. a race pace. RFE is largely determined by RPE, however, the relationship between the two is not directly linked, with many aspects, specifically positivity and negativity, being able to alter the link between the two, i.e. swing the arrow up or down. The RFE Fatigue model also ‘fits in nicely’ with most marathon runner’s experiences, i.e. that towards the end of the race, they run out of energy. Remember, this is no longer carbohydrate / biochemical energy, but more likely Race Focus Energy, or simply mental energy.

Therefore to improve performance during an endurance event such as a marathon, one either has to ensure RPE doesn’t reach maximal levels, or alternatively adopting the RFE Fatigue Model, ensure one does not empty their RFE tank prior to the finish line. At first I will disregard the impact of positivity/negativity and simply look at RFE as being directly determined by RPE. Then if I aren’t too fatigued I will attempt to introduce where positivity and negativity fits in.

The key idea behind an equal paced marathon running strategy is for the “power output” as Tom describes it, to remain even throughout the entire race. With even power output on a flat course translating to even running pace, i.e. constant minute per mile rate, and subsequently equal half marathon split times. The only problem with this idea is that an even pace throughout a marathon does not mean you are running at an even physiological intensity. Due to a number of physiological aspects that occur as the duration of the race increases, such as dehydration, muscles gradually fatiguing, and possible changes in fuel utilisation towards an increase in fat burning (which requires more oxygen for the same ATP generation), there is an increase in the physiological load for the same power output / running pace, which is known as cardiac drift. Runners will be well aware of this if they race with a heart rate monitor, as they will observe a gradual increase in heart rate throughout the race, with the increase being greater during the latter stages of the race, even if they maintain a constant running pace.

Runners who don’t use a heart rate monitor will also be well aware of this phenomenon when reflecting on how ‘hard’ the race was, as their Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE) increases as the duration of the race progresses when running at a constant pace. Typically, if adopting a constant pace strategy, their RPE would be low at the start of the race, maybe around 11(Light) – 13 (Somewhat Hard), and then progressively increases up towards 17(Very Hard) – 19 (Extremely Hard) during the latter stages of the race. An increase in RPE therefore results in an increased usage rate of RFE. The figure below is taken from Parry et al., 2011. An article on perceived exertion among Ironman triathletes, within November's edition of BJSM. The figure clearly shows how the RPE increases during the marathon (of an Ironman), even though the actual running pace decreases as the marathon progresses. (The decrease in running speed is not clearly illustrated by the poor scale on the axis, up to 30 km/hr!) It looks like the pace has dropped from around 10.1 km/hr (5:56 per km) down to around 8.8 km/hr (6:49 per km). Therefore to maintain an even running pace throughout the entire marathon would require an even larger rise in RPE than illustrated within the figure below.

I guess the ‘million dollar’ question is, “Is this progressive increase in intensity, from light at the start, up to hard at the end, really the best pacing strategy?” If we look at the strategy to reduce the likelihood of emptying one’s RFE tank, then one would conclude that starting at an easy pace, where the RFE usage is low at the start, would lessen the chance of running out of RFE before the end of the race. However, due to running at a lower intensity, this means you are actually running slower than what you could have run at. The theory behind the even power output is that because you have taken the first half easy, i.e. with minimal Race Focus Energy, then you are more likely to be able to maintain the same running pace during the second half of the race, as your RFE tank will be substantially fuller than if you had started with a higher intensity, at a higher usage of RFE.

The even power output strategy therefore looks good. However, what happens during the second half of the race? Remember an even power output strategy (even running pace on a flat course) means you have run at a slower pace than you could have achieved, so you have time to make up in order to cross the finish line in a quicker time. What it gets down to is how much extra RFE will you consume during the second half of the race in order to maintain the same running pace, over and above the amount you would have consumed, if you had started running initially at a higher intensity, therefore at a quicker running pace, and therefore having the ‘luxury’ of being able to reduce your pace during the second half, and hence use less RFE? As just highlighted, the benefit of starting at a quicker pace is that you are able to keep the RFE usage, (or the RPE value), the same during the second half of the race, as you have ‘time up your sleeve’ so therefore able to allow the pace to drop gradually to equally match the gradual increase in physiological load as a result of cardiac drift.

The confusion often arises because it is assumed that starting at a quicker pace, i.e. quicker than what you are capable of maintaining for the entire duration of the race, means that you are working at a higher physiological intensity, higher than what you could maintain for the entire duration of the race. This assumption is incorrect. By starting at a quicker pace, you are actually keeping the physiological loading, the intensity, the RPE, and most importantly the RFE at a more even value! It is attempting to run at an even pace, with an even power output, that results in large variations in physiological loading, RPE and RFE. It is typically assumed for most variables that an even constant value is more efficient than fluctuations or a wide range of values. So YES adopting an even strategy is the answer, but not an even running pace, or an even power output strategy, but a strategy that results in an even physiological intensity, and an even usage of Race Focus Energy!,

Looking at the example of a runner adopting an even power output strategy, means the runner has taken it easy at the start, running slower than one could quite easily have run at, as there is no fatigue, heart rate is therefore the lowest it will be throughout the entire race before cardiac drift, and their RPE will also be at the lowest, as this continuously rises during the race, as clearly illustrate in the figure above. However, will they actually be able to translate having a fuller tank of RFE leading into the second half of the race into actually maintaining the same even running pace? Before answering this question, there is one aspect that I haven’t mentioned yet: muscle fatigue / muscle damage. The muscular force required from your lower limbs to run is typically in the region of around 20% of one’s maximal force value that they can generate. Now during endurance running, as muscles gradually fatigue, the decline in the muscle force that is able to be generated actually plateaus, at a level of around 30 - 40% decrease. So even at the end of ultra races, the muscles are still able to generate 60 - 70% of their maximal force, which you can see is significantly more than the 20% that is needed to run. So the muscle fatiguing aren’t actually the limiting factor. They simply cause the running to be less efficient, hence the drift upwards in heart rate, RPE and therefore increased RFE usage, at the same running pace.

The problem during marathon / ultra running is actually the muscle damage, the increased pain the runner feels as the race progresses, on each and every foot strike. This pain is usually worse on the down hills where the muscles are contracting eccentrically (i.e. the muscle lengthens as it contracts) and also during road racing, where there isn’t the same ‘give’ in the road as there is on the trails. So during the latter periods of endurance races, such as a marathon, although the runner that started at an easy pace has more RFE in the tank, the usage rate is now magnified immensely simply due to the pain from the muscle damage. If you reflect back to your last marathon or ultra race, how much mental focus did it take to keep moving at a reasonable pace when your legs were ‘screaming’ for you to stop? There was most likely increased RFE usage simply due to the muscle damage pain! Yes, if your experiences were similar to my typical experience in an ultra race, then it probably took significantly higher levels of RFE to maintain the same pace. Not due to a lack of physiological fitness such as VO2 max, or lactate threshold, but simply due to the muscle damage that is unavoidable in endurance racing. One could suggest that the muscle damage would be more if the runner runs the first half of the race at a faster pace, however, the muscle damage is much more time/duration dependent rather than pace dependent, especially when running on the trails, where the running pace effect on muscle damage is even much smaller. It isn’t just muscle damage that can cause the RFE usage to significantly increase during the latter stages of the race. Other factors such as blisters, cramps, dehydration, overheating, stomach/digestion issues etc, can all increase significantly the amount of Race Focus Energy that is required in order to maintain the same running pace.

Hopefully it is becoming clearer in terms of ‘where I am coming from’! Slowing down during the second half of a marathon isn’t solely determined by the pace the runner runs the first half in. Yes, it does play a part, as a quicker pace will have used up more RFE, but during the second half of the race, there are so many other factors that can significantly increase the RFE usage rate, which far exceeds any ‘savings’ achieved by running at an easy pace during the first half. Those runners that are able to maintain an even paced marathon, or even a negative split, in some ways are achieving it, perhaps one could say by as much a little bit of luck, as opposed to their physical preparation (which plays an important role – but another post), or more specific to this post, as opposed to their conservative running pace in the first half. The easy running pace during the first half I believe plays only a little part in everything seeming to ‘fall into place’, i.e. that they didn’t cramp, didn’t get dehydrated, didn’t get blisters, didn’t get overly painful muscle damage etc., and with the easy running pace during the first half I would suggest most likely does not have such a large affect, that it was worth ‘wasting’ the opportunity to run faster while they could, before these multitude of potential problems possibly arise during the second half. Hence my philosophy; “Run as fast as you can, WHILE you can!” Before the muscle damage, dehydration, etc. massively increases the rate of RFE usage!

Although I haven’t even touched on the role of positivity and negativity above, (another post), now is a good time to look at some actual race data. Is this ability to run an even running pace in a marathon, or even better, to run a negative split, actually an indication of a good performance, of being a better runner? Is it a quality of better runners, such as one may associate a high VO2 max or lactate threshold as a quality of better runners? And secondly, how many runners actually achieve this so called ‘great running performance’ to achieve a negative split. If you achieved it, would you therefore be within the ‘quality’ runners that make up say 10% of all runners, or is this quality performance not that distinctive, and in fact you are just one of say 20% of all runners. Still an aspiration to aspire to, to be within the ‘best’ 20% of the field, as remember, the negative split is portrayed as THE achievement!

To help answer these questions I looked at the results from this year’s Virgin London Marathon. Perhaps as one would expect, based on the status the negative split has, both the male and female winners ran negative splits. So therefore why have I wasted all of this time typing up this blog post, attempting to get you to consider that the negative split isn’t what it is made out to be? But let’s look a little deeper at the results. How many of the other 99 runners in the top 100 in the massed start race also achieved a negative split? Remember these runners are the very best, at the very front of a field of over 35,000 finishers. Surely then one would expect around half of the top 100, or at least a third! No, only seven other runners in the top 100 finishers ran a negative split. This ‘strange’ result could however be because at the front of the race many of the runners went out with the pace makers at nearly world record pace, in the hope of hanging in there to the finish, they therefore were never going to achieve a negative split. So if I look at how many within the next 100 places from 101 – 200 achieved a negative split, this would give perhaps a more true representation of the frequency of the negative split occurring. These runners from 101 – 200 are still top quality runners, and in relation to the overall field, very, very fast runners, with an average finish time of 2 hours 39 minutes. The results show that there were only 6 negative split runners from the 100.

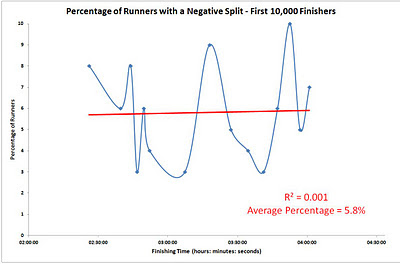

If you look at the following graph, that shows the number of runners that negative split from samples of 100 runners at different time gaps for the first 10,000 finishers, then you will see that there is ABSOLUTELY no relationship at all between the finish time of the runners and the percentage that achieve a negative split. If running a negative split was a quality of being a good runner, of a good performance, then surely one would expect that further towards the front of the field there would be a higher percentage? With a correlation of pretty well zero, one shouldn’t need any more evidence that the negative split is NOT something to aim for, NOT something that indicates that you performed well!

Another key statistic is the percentage of runners within the first 10,000 finishers that actually achieve it, being only 5.8%. With this evidence it therefore still amazes me that there seems to be the message ‘out there’ that the negative split is something all runners should aim for. If we look at a 10% sample, in batches of 100 runners, spread throughout the 23,600 runners that finished within 5 hours at London, then the percentage that achieve a negative split drops even lower to only 4.3% of finishers! The following graph also show how the positive split slowing down time increases as the finishing time increases.

A really issue that needs attention is in terms of the potential effect this low percentage of negative splits may have on the marathon finishers, when 95.7% of them do not achieve probably the number one goal that is drummed into them apart from finishing! Remember the message ‘out there’ that the negative split indicates that you ran well, probably even more important than your actual finishing time. So 95.7% of runners are potentially disappointed because they didn’t achieve one of their goals. So if they do another marathon, which hopefully they will still want to, even after the disappointment of not negative splitting, then what do you think their likely race strategy will be for their next marathon? Well I would suspect that they would likely run the first half of the next marathon at an even slower, easier pace, as they possibly would have concluded that the reason that they didn’t achieve the negative split is that they started off too fast, and therefore that is why they ran out of energy. Which they may associate as running out of carbohydrate energy, as it is reasonably well known within the running community that the higher the physiological intensity, the greater the usage of carbohydrate. But remember that is the old model of endurance fatigue, before gels were available. Carbohydrate depletion is no longer the cause of fatigue in marathon runners.

As I have mentioned above, fatigue is more likely a consequence of RPE, or specifically getting close to emptying the tank of Race Focus Energy. As many runners are not aware of the latest fatigue research which is based on the Central Governor, i.e. the brain, it is probable that most runners are likely to conclude that their running pace being too fast at the start was probably the cause of their fatigue! And as I have highlighted above, the rate of RFE usage during the second half of a marathon is determined by much, much more than one’s running pace during the first half of the race. So starting their subsequent marathon at an even slower running pace, doesn’t guarantee that they will achieve this much wanted negative split goal, as demonstrated by only 4.3% of runners finishing in less than 5 hours achieving it.

Well, time to take a breathe! Phew, I think I have definitely got this negative split ‘dislike’ off my chest!

I think now is an appropriate time to call it a night. Hopefully those of you that have reached this far, have found something worthwhile within this blog, once you manage to navigate past the occasional frustration that may be evident within my writing. Please feel free to leave me a comment, explaining where I have gone astray, where I have got it wrong. I’m not saying that my ideas must be right, probably on most occasions, the majority of you would conclude that my ideas are a bit ‘far-fetched’, however, with regards to pacing strategy, hopefully I have at least got you questioning that maybe it is the negative split concept that this time is too ‘far-fetched’!

I will sign off with a quote from Tom Williams from MarathonTalk, which was within the comment he left on last week’s race report post:

Stuart

Tonight’s post, as the title indicates, is about Pacing Strategy, and specifically, does a negative split improve performance? Part of my Dorset Trail Marathon race report last week included a bit of a ‘rant’ about how I felt that the negative split resulted in slower finishing times, not quicker as suggested by many, including Martin and Tom from MarathonTalk. Well following my post it was pleasing to know that both Martin and Tom read my race report with them both leaving a comment on the blog. I especially liked Tom’s quote "I'd rather know I was wrong than think I was right". So it got me questioning what is it that makes me think that I am right, that makes me believe that the negative split is the wrong strategy? So hopefully tonight I will provide some material to confirm my beliefs, but I guess the real purpose, as with most of my blog posts, is to encourage you the reader, to question your approach to running, to consider alternative approaches, even if they are not in agreement with the accepted norm, and at first impressions appear a ‘bit too far out of the box’!

The starting point is first to confirm what causes fatigue during endurance running performance. As mentioned in previous posts, fatigue in the past used to be considered to be due to peripheral fatigue, for marathons, typically due to glycogen/carbohydrate depletion. With the availability of carbohydrate gels, fatigue in marathons now seldom occurs due to low blood glucose levels, as evidenced by the frequent sight from the 1980s of jelly legged runners stumbling towards the finish line of the London Marathon, now a very rare occurrence. The latest research, initiated by Professor Tim Noakes, highlights the importance of the brain (The Central Governor) and more specifically the integral role of RPE (Rating of Perceived Exertion). While doing physical activity, the runner rates their perception of exertion, i.e. their feeling of how heavy and strenuous the exercise feels, combining all sensations and feelings of physical stress, effort, and fatigue. This rating, typically known as the Borg Scale 6-20, (as there is also an alternative 1 – 10 scale) ranges from 6 (no exertion at all) up to 20 (maximal exertion), has been shown within the scientific research to be a stronger predictor of fatigue than any physiological measurements. The latest fatigue models within the scientific literature therefore propose that fatigue within endurance events occur once a maximal RPE is reached. Therefore during the marathon one should have a strategy that prevents one’s RPE from reaching maximum levels prior to the finish line.

Although I accept that RPE is the core component that contributes to fatigue during endurance events, the concept that maximal RPE must occur in order for fatigue to take place, in my experiences doesn’t seem to ‘fit’. During the latter stages of ultra races and marathons, I am not really working at a very high intensity, so I am therefore not experiencing maximal levels of physical stress, although there are high levels of effort, although this is what would typically be classified as mental effort. If one takes on board a ‘fuller/wider’ interpretation of RPE, more than the physical stress/fatigue, then I suppose the maximal RPE concept contributing to fatigue can apply. However, I prefer the introduction of a new theoretical measure known as RFE (Race Focus Energy). Where RFE is a measure of the mental effort, the concentration, the race focus required in order to keep running at a fast pace, i.e. a race pace. RFE is largely determined by RPE, however, the relationship between the two is not directly linked, with many aspects, specifically positivity and negativity, being able to alter the link between the two, i.e. swing the arrow up or down. The RFE Fatigue model also ‘fits in nicely’ with most marathon runner’s experiences, i.e. that towards the end of the race, they run out of energy. Remember, this is no longer carbohydrate / biochemical energy, but more likely Race Focus Energy, or simply mental energy.

Therefore to improve performance during an endurance event such as a marathon, one either has to ensure RPE doesn’t reach maximal levels, or alternatively adopting the RFE Fatigue Model, ensure one does not empty their RFE tank prior to the finish line. At first I will disregard the impact of positivity/negativity and simply look at RFE as being directly determined by RPE. Then if I aren’t too fatigued I will attempt to introduce where positivity and negativity fits in.

The key idea behind an equal paced marathon running strategy is for the “power output” as Tom describes it, to remain even throughout the entire race. With even power output on a flat course translating to even running pace, i.e. constant minute per mile rate, and subsequently equal half marathon split times. The only problem with this idea is that an even pace throughout a marathon does not mean you are running at an even physiological intensity. Due to a number of physiological aspects that occur as the duration of the race increases, such as dehydration, muscles gradually fatiguing, and possible changes in fuel utilisation towards an increase in fat burning (which requires more oxygen for the same ATP generation), there is an increase in the physiological load for the same power output / running pace, which is known as cardiac drift. Runners will be well aware of this if they race with a heart rate monitor, as they will observe a gradual increase in heart rate throughout the race, with the increase being greater during the latter stages of the race, even if they maintain a constant running pace.

Runners who don’t use a heart rate monitor will also be well aware of this phenomenon when reflecting on how ‘hard’ the race was, as their Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE) increases as the duration of the race progresses when running at a constant pace. Typically, if adopting a constant pace strategy, their RPE would be low at the start of the race, maybe around 11(Light) – 13 (Somewhat Hard), and then progressively increases up towards 17(Very Hard) – 19 (Extremely Hard) during the latter stages of the race. An increase in RPE therefore results in an increased usage rate of RFE. The figure below is taken from Parry et al., 2011. An article on perceived exertion among Ironman triathletes, within November's edition of BJSM. The figure clearly shows how the RPE increases during the marathon (of an Ironman), even though the actual running pace decreases as the marathon progresses. (The decrease in running speed is not clearly illustrated by the poor scale on the axis, up to 30 km/hr!) It looks like the pace has dropped from around 10.1 km/hr (5:56 per km) down to around 8.8 km/hr (6:49 per km). Therefore to maintain an even running pace throughout the entire marathon would require an even larger rise in RPE than illustrated within the figure below.

I guess the ‘million dollar’ question is, “Is this progressive increase in intensity, from light at the start, up to hard at the end, really the best pacing strategy?” If we look at the strategy to reduce the likelihood of emptying one’s RFE tank, then one would conclude that starting at an easy pace, where the RFE usage is low at the start, would lessen the chance of running out of RFE before the end of the race. However, due to running at a lower intensity, this means you are actually running slower than what you could have run at. The theory behind the even power output is that because you have taken the first half easy, i.e. with minimal Race Focus Energy, then you are more likely to be able to maintain the same running pace during the second half of the race, as your RFE tank will be substantially fuller than if you had started with a higher intensity, at a higher usage of RFE.

The even power output strategy therefore looks good. However, what happens during the second half of the race? Remember an even power output strategy (even running pace on a flat course) means you have run at a slower pace than you could have achieved, so you have time to make up in order to cross the finish line in a quicker time. What it gets down to is how much extra RFE will you consume during the second half of the race in order to maintain the same running pace, over and above the amount you would have consumed, if you had started running initially at a higher intensity, therefore at a quicker running pace, and therefore having the ‘luxury’ of being able to reduce your pace during the second half, and hence use less RFE? As just highlighted, the benefit of starting at a quicker pace is that you are able to keep the RFE usage, (or the RPE value), the same during the second half of the race, as you have ‘time up your sleeve’ so therefore able to allow the pace to drop gradually to equally match the gradual increase in physiological load as a result of cardiac drift.

The confusion often arises because it is assumed that starting at a quicker pace, i.e. quicker than what you are capable of maintaining for the entire duration of the race, means that you are working at a higher physiological intensity, higher than what you could maintain for the entire duration of the race. This assumption is incorrect. By starting at a quicker pace, you are actually keeping the physiological loading, the intensity, the RPE, and most importantly the RFE at a more even value! It is attempting to run at an even pace, with an even power output, that results in large variations in physiological loading, RPE and RFE. It is typically assumed for most variables that an even constant value is more efficient than fluctuations or a wide range of values. So YES adopting an even strategy is the answer, but not an even running pace, or an even power output strategy, but a strategy that results in an even physiological intensity, and an even usage of Race Focus Energy!,

Looking at the example of a runner adopting an even power output strategy, means the runner has taken it easy at the start, running slower than one could quite easily have run at, as there is no fatigue, heart rate is therefore the lowest it will be throughout the entire race before cardiac drift, and their RPE will also be at the lowest, as this continuously rises during the race, as clearly illustrate in the figure above. However, will they actually be able to translate having a fuller tank of RFE leading into the second half of the race into actually maintaining the same even running pace? Before answering this question, there is one aspect that I haven’t mentioned yet: muscle fatigue / muscle damage. The muscular force required from your lower limbs to run is typically in the region of around 20% of one’s maximal force value that they can generate. Now during endurance running, as muscles gradually fatigue, the decline in the muscle force that is able to be generated actually plateaus, at a level of around 30 - 40% decrease. So even at the end of ultra races, the muscles are still able to generate 60 - 70% of their maximal force, which you can see is significantly more than the 20% that is needed to run. So the muscle fatiguing aren’t actually the limiting factor. They simply cause the running to be less efficient, hence the drift upwards in heart rate, RPE and therefore increased RFE usage, at the same running pace.

The problem during marathon / ultra running is actually the muscle damage, the increased pain the runner feels as the race progresses, on each and every foot strike. This pain is usually worse on the down hills where the muscles are contracting eccentrically (i.e. the muscle lengthens as it contracts) and also during road racing, where there isn’t the same ‘give’ in the road as there is on the trails. So during the latter periods of endurance races, such as a marathon, although the runner that started at an easy pace has more RFE in the tank, the usage rate is now magnified immensely simply due to the pain from the muscle damage. If you reflect back to your last marathon or ultra race, how much mental focus did it take to keep moving at a reasonable pace when your legs were ‘screaming’ for you to stop? There was most likely increased RFE usage simply due to the muscle damage pain! Yes, if your experiences were similar to my typical experience in an ultra race, then it probably took significantly higher levels of RFE to maintain the same pace. Not due to a lack of physiological fitness such as VO2 max, or lactate threshold, but simply due to the muscle damage that is unavoidable in endurance racing. One could suggest that the muscle damage would be more if the runner runs the first half of the race at a faster pace, however, the muscle damage is much more time/duration dependent rather than pace dependent, especially when running on the trails, where the running pace effect on muscle damage is even much smaller. It isn’t just muscle damage that can cause the RFE usage to significantly increase during the latter stages of the race. Other factors such as blisters, cramps, dehydration, overheating, stomach/digestion issues etc, can all increase significantly the amount of Race Focus Energy that is required in order to maintain the same running pace.

Hopefully it is becoming clearer in terms of ‘where I am coming from’! Slowing down during the second half of a marathon isn’t solely determined by the pace the runner runs the first half in. Yes, it does play a part, as a quicker pace will have used up more RFE, but during the second half of the race, there are so many other factors that can significantly increase the RFE usage rate, which far exceeds any ‘savings’ achieved by running at an easy pace during the first half. Those runners that are able to maintain an even paced marathon, or even a negative split, in some ways are achieving it, perhaps one could say by as much a little bit of luck, as opposed to their physical preparation (which plays an important role – but another post), or more specific to this post, as opposed to their conservative running pace in the first half. The easy running pace during the first half I believe plays only a little part in everything seeming to ‘fall into place’, i.e. that they didn’t cramp, didn’t get dehydrated, didn’t get blisters, didn’t get overly painful muscle damage etc., and with the easy running pace during the first half I would suggest most likely does not have such a large affect, that it was worth ‘wasting’ the opportunity to run faster while they could, before these multitude of potential problems possibly arise during the second half. Hence my philosophy; “Run as fast as you can, WHILE you can!” Before the muscle damage, dehydration, etc. massively increases the rate of RFE usage!

Although I haven’t even touched on the role of positivity and negativity above, (another post), now is a good time to look at some actual race data. Is this ability to run an even running pace in a marathon, or even better, to run a negative split, actually an indication of a good performance, of being a better runner? Is it a quality of better runners, such as one may associate a high VO2 max or lactate threshold as a quality of better runners? And secondly, how many runners actually achieve this so called ‘great running performance’ to achieve a negative split. If you achieved it, would you therefore be within the ‘quality’ runners that make up say 10% of all runners, or is this quality performance not that distinctive, and in fact you are just one of say 20% of all runners. Still an aspiration to aspire to, to be within the ‘best’ 20% of the field, as remember, the negative split is portrayed as THE achievement!

To help answer these questions I looked at the results from this year’s Virgin London Marathon. Perhaps as one would expect, based on the status the negative split has, both the male and female winners ran negative splits. So therefore why have I wasted all of this time typing up this blog post, attempting to get you to consider that the negative split isn’t what it is made out to be? But let’s look a little deeper at the results. How many of the other 99 runners in the top 100 in the massed start race also achieved a negative split? Remember these runners are the very best, at the very front of a field of over 35,000 finishers. Surely then one would expect around half of the top 100, or at least a third! No, only seven other runners in the top 100 finishers ran a negative split. This ‘strange’ result could however be because at the front of the race many of the runners went out with the pace makers at nearly world record pace, in the hope of hanging in there to the finish, they therefore were never going to achieve a negative split. So if I look at how many within the next 100 places from 101 – 200 achieved a negative split, this would give perhaps a more true representation of the frequency of the negative split occurring. These runners from 101 – 200 are still top quality runners, and in relation to the overall field, very, very fast runners, with an average finish time of 2 hours 39 minutes. The results show that there were only 6 negative split runners from the 100.

If you look at the following graph, that shows the number of runners that negative split from samples of 100 runners at different time gaps for the first 10,000 finishers, then you will see that there is ABSOLUTELY no relationship at all between the finish time of the runners and the percentage that achieve a negative split. If running a negative split was a quality of being a good runner, of a good performance, then surely one would expect that further towards the front of the field there would be a higher percentage? With a correlation of pretty well zero, one shouldn’t need any more evidence that the negative split is NOT something to aim for, NOT something that indicates that you performed well!

Another key statistic is the percentage of runners within the first 10,000 finishers that actually achieve it, being only 5.8%. With this evidence it therefore still amazes me that there seems to be the message ‘out there’ that the negative split is something all runners should aim for. If we look at a 10% sample, in batches of 100 runners, spread throughout the 23,600 runners that finished within 5 hours at London, then the percentage that achieve a negative split drops even lower to only 4.3% of finishers! The following graph also show how the positive split slowing down time increases as the finishing time increases.

A really issue that needs attention is in terms of the potential effect this low percentage of negative splits may have on the marathon finishers, when 95.7% of them do not achieve probably the number one goal that is drummed into them apart from finishing! Remember the message ‘out there’ that the negative split indicates that you ran well, probably even more important than your actual finishing time. So 95.7% of runners are potentially disappointed because they didn’t achieve one of their goals. So if they do another marathon, which hopefully they will still want to, even after the disappointment of not negative splitting, then what do you think their likely race strategy will be for their next marathon? Well I would suspect that they would likely run the first half of the next marathon at an even slower, easier pace, as they possibly would have concluded that the reason that they didn’t achieve the negative split is that they started off too fast, and therefore that is why they ran out of energy. Which they may associate as running out of carbohydrate energy, as it is reasonably well known within the running community that the higher the physiological intensity, the greater the usage of carbohydrate. But remember that is the old model of endurance fatigue, before gels were available. Carbohydrate depletion is no longer the cause of fatigue in marathon runners.

As I have mentioned above, fatigue is more likely a consequence of RPE, or specifically getting close to emptying the tank of Race Focus Energy. As many runners are not aware of the latest fatigue research which is based on the Central Governor, i.e. the brain, it is probable that most runners are likely to conclude that their running pace being too fast at the start was probably the cause of their fatigue! And as I have highlighted above, the rate of RFE usage during the second half of a marathon is determined by much, much more than one’s running pace during the first half of the race. So starting their subsequent marathon at an even slower running pace, doesn’t guarantee that they will achieve this much wanted negative split goal, as demonstrated by only 4.3% of runners finishing in less than 5 hours achieving it.

Well, time to take a breathe! Phew, I think I have definitely got this negative split ‘dislike’ off my chest!

I think now is an appropriate time to call it a night. Hopefully those of you that have reached this far, have found something worthwhile within this blog, once you manage to navigate past the occasional frustration that may be evident within my writing. Please feel free to leave me a comment, explaining where I have gone astray, where I have got it wrong. I’m not saying that my ideas must be right, probably on most occasions, the majority of you would conclude that my ideas are a bit ‘far-fetched’, however, with regards to pacing strategy, hopefully I have at least got you questioning that maybe it is the negative split concept that this time is too ‘far-fetched’!

I will sign off with a quote from Tom Williams from MarathonTalk, which was within the comment he left on last week’s race report post:

“A large amount of what we achieve is governed by our mental state and how we see ourselves. (It is) a lot about opening the mind to what might be possible when we throw away the self imposed limitations of our mind.” Tom Williams, 2011.All the best with the formulation of your pacing strategy for your next race. Remember, whatever strategy you adopt, you must have total belief that it is the right strategy that works for you.

Stuart

Saturday, 10 December 2011

Endurancelife Dorset Coastal Trail Marathon - Race Report - Self Expectations Influence Performance

Hi,

If you have come to my blog for the first time to read my Endurancelife Dorset Coastal Trail Marathon race report, welcome, I hope you find your visit to my blog worthwhile. You will see from the length of my posts that they reflect the running that I do, i.e. marathon and ultra distance durations. So you will require reasonably high levels of endurance to manage to reach the end of each and every post!

One of the key benefits I get from writing my blog posts is that it provides quality time to reflect on my training and racing, in order to improve in subsequent races. I feel my performance in last weekend’s Dorset trail marathon, which I was pretty pleased with, was largely a consequence of the time I spent reflecting on my performance in my last race, the Beachy Head Marathon. It was in the process of analysing my performance in the Beachy Head Marathon, where I finished in 2nd place, but in a time 30 seconds slower than the year before, combined with the development of my Race Focus Energy Fatigue Model, where I identified what was required in order to produce a successful performance down in Dorset. With success being defined as a performance I am happy with, i.e. where I feel as if I have run as well as I can (yes, a rather vague criteria, which I will hopefully expand upon).

So as I prepared for the race, the key aim was to run hard and focused for the entire 26.6 miles (the distance advertised on the Endurancelife website and what my Garmin 305 watch indicated on the day). This desire to remain focused the entire way was in direct response to how I raced at the Beachy Head marathon, where I eased of the pace in order to unsuccessfully prepare for a tactical battle with the eventual winner. On reflection, easing off the pace between miles 19 – 23 resulted in me not able to feel totally satisfied with my performance. I guess if I had won the race I would have traded the easing off the pace, with the satisfaction of winning. Well that was the rationale I accepted, as I ‘gave in’ to the messages ‘bombarding’ me to slow down during the race.

Leading up to the Dorset race extensive time was spent firstly clearly establishing answers to the initial three questions one has to answer when preparing for a race; What do I want? Why do I want it? How much do I want it? In order to answer these questions I had to be totally aware of what the race would entail, so then I would be able to determine / visualise how I would respond to the demands of the race. I therefore purchased an Ordinance Survey map, and transferred the course from the map downloaded from the website, onto the larger scaled map. The time spent doing this is a critical component of my preparation. It allows me to get ingrained into my subconscious the overall plan of the course, as if looking from above. I am therefore aware in what direction I should be heading, whether there are any 90degree turns, any out and backs, parts where we retrace the same path, etc. It basically gives me an overall feel of the route, at a deep level. During the race, just having this plan view of the course firmly ingrained, totally eliminated any doubt there could have been, just after the turnaround point where there was some confusion over which way to go. I simply referred to the visual image I had of the route map within my head, and was able to progress along the correct route, without there being any doubt at all, so thereby avoiding any upward swing of the RPE – RFE arrow (see previous Race Focus Energy posts).

In addition to marking the route on the map, I also carefully observe the number of contour lines I cross and the closeness of the lines, hence the steepness of the climbs. I also note the height at the peak of the climbs, so therefore get a feel for the elevation demands of the course. Further time is also spent trying to find photos of the area, which is combined with viewing the map, and a fly over the course on Google Earth, using the GPS file provided by the Endurancelife organisers on the website. The hours I spend doing this research / preparation, I consider are as beneficial, if not more beneficial to my performance than spending the same time running. The graph below clearly shows the rather demanding elevation profile!

Based on all of the above research, I was then able to have a rough prediction that I would be running for around 3 hours 40 minutes. Having a reasonable calculated idea of the time duration of the race is important, as the time duration expectation controls the pace you are able to run at. If there is doubt over the expected race duration, then this uncertainty increases the level of the reserve portion of the RFE tank, as well as swinging the RPE – RFE arrow upwards. Both of these aspects reduce your performance.

Race day arrived and I felt confident that my preparation had gone well, so I was therefore expecting a strong performance. In terms of my physical training, well I hadn’t actually done that much since UTMB way back in August - checking the training diary, only 453 miles at an average of 32.4 miles per week. However, having close to 40,000 miles of running within my legs, I knew my recent physical training wasn’t really going to limit my performance, and with this belief, my confidence and race expectations were high come race day. One of the key messages I try to get across within my talks is that one of the main purposes of physical training is simply to create confidence that one’s preparation has gone well, the physiological benefits of additional/high levels of physical training are probably secondary in comparison to the confidence benefits.

Over the last year I have been listening to the MarathonTalk Podcasts http://www.marathontalk.com/ If you haven’t come across MarathonTalk, then you really should give their website a visit. The podcasts consist of two guys, Martin Yelling and Tom Williams chatting about running, combined with a great interview each week. This week was the 100th edition, so there is loads of really excellent material within the podcasts. Well anyway, over the last few weeks there had been a bit of talk about Martin Yelling racing the Endurancelife Dorset Coastal Trail Marathon. Now Martin is an elite athlete, I think a sub 30 minute 10km runner, as well as I think a double National Duathlon Champion. However, listening to him and Tom chat, it appears that they place far too much emphasis on one’s recent levels of physical training. Therefore leading up to the race, one could sense that Martin no longer considered himself as an elite athlete, even though he had just completed a 5km Park Run in close to 16 minutes, whereas I would be struggling to get close to 17 minutes based on my current physical preparation! So as the race got closer my village training partner Kev, who got me into listening to MarathonTalk , every Saturday morning would ask me “Are you going to take down Martin Yelling?” In most instances when people ask me am I going to win a race, I always reply that I cannot control how other runners perform, so unable to answer. But to Kev’s question, I was able to answer, yes, no problem, should do. This response was nothing to do with Martin’s physical capabilities, which on paper were superior than mine, but by listening to his self expectations. It appeared that he no longer considered himself as an elite athlete, he felt that he had under prepared, and therefore as one performs to their expectations, there was no way he was going to beat me, as his belief in his under preparations would most likely result in him under performing! I had felt my preparation had gone well, my confidence was high, and knowing that race performance in trail marathons and ultras is determined by more than the physical, I had a strong feeling that it wasn’t going to be a close contest!

Well, I did warn you at the start of this post that you would need marathon endurance to get through my blog posts! One reason my posts are so long is that I log all the time I spend typing up the posts as training. So the more I type, the more training I have completed, so therefore increased confidence leading into a race, due to extensive time conducting TOTAL preparation!

There are around 150 starters gathered at the start line near Osmington, not far from Weymouth. The course heads east, along the coast, with a strong tailwind for around 14 miles, before coming back on a less undulating route, slightly in from the coast. As the course within 100 metres from the start crosses a style and then shortly after goes onto single track, Endurancelife opt for a dibber start, where as you cross the start line you have to dib your dibber. This prevents the frustration of getting stuck in a ‘traffic jam’ as it takes around two minutes for all runners to start, thereby spacing the runners out. At the front of the field it makes the start of the race have a different feel, as immediately the lead bunch is down to less than ten runners. I cross the first stile after 100 metres of uphill leading the small bunch, and then decide to stretch the legs out a bit.

If you have looked at my two previous posts http://ultrastu.blogspot.com/2011/10/beachy-head-marathon-illustration-of.htmland http://ultrastu.blogspot.com/2011/11/delamere-spartans-weekend-bit-more-on.html on my Race Focus Energy (RFE) Fatigue Model then hopefully you have an understanding that I believe that performance in trail marathons and ultra trail races is determined by the rate of usage of RFE during the race, in relation to the size of the RFE tank. There are different strategies runners adopt when running marathons, and most of them are based on the outdated model of fatigue in endurance events, i.e. fatigue is due to depletion of carbohydrate/glycogen, or due to lactic acid! The latest research has clearly shown that this concept in most cases is incorrect (unless you don’t take on carbohydrate during racing). It is now widely accepted (initially proposed by Professor Tim Noakes) that fatigue in endurance events is a consequence of a decrease in muscle activation, controlled by the brain, which is strongly influenced by one’s rating of perceived exertion (RPE). My RFE model has this latest research, i.e. RPE, at its core, however, it also takes into account all of the other factors that influence performance such as confidence, self belief, positivity, negativity, excitement, enjoyment, encouragement etc.

I therefore run hard right from the very start of the race, working at a high level, not directly monitoring my physical intensity (RPE), but monitoring the current usage of RFE. The two are related, but it is the RFE that is most important. My aim is to try to maintain a constant level of RFE usage throughout the race, so this means that my mental effort/focus is identical in the first mile to what it is during the last mile. This is a totally different concept to the typical advice one reads within running magazines, and even the advice that Martin and Tom give out on Marathon Talk, i.e. to run at an easy pace to half way, so at half way you feel comfortable so able to ‘handle’ the second half of the race when things get ‘tough’. It is interesting, that in all of the MarathonTalk podcasts I have listened to, which are quite a few now, this one concept on marathon pacing, is pretty well the only bit of advice Martin and Tom have given that I don’t agree with. I just can’t understand how they can have such good ideas on all other aspects of running, training, nutrition, preparation etc. but yet get this concept, in my opinion, so, so wrong! The idea of a negative split that they frequently highlight and encourage, appears to me to be unattainable if running to your true capabilities by runners apart from the very, very elite. Yes, there are ‘middle of the pack’ runners that achieve a negative split in a marathon, but rather than celebrating this, I think one should question how have they achieved it. Most likely due to running so slowly in the first half of the race, resulting in their overall time being significantly slower than it would have been if they had attempted to focus for the entire duration of the race. In essence, I see the negative split argument, i.e. take it easy to halfway, As an acknowledging that one’s preparation has not been adequate, in that one doesn’t have the confidence to focus for the whole race, so they are turning the marathon into a half marathon. The unconfident runner runs at training pace for the first half, and then starts to race, starts to focus after half way, due to only having the confidence that one is able to race/focus for half the distance!

Sorry about the previous paragraph. I just had to get that ‘off my chest’, as it really bugs me that so many runners believe the equal running pace concept for marathon running, and therefore I feel perform at a level so much lower than what they could be capable of, if they had used a different pacing strategy! Anyway back to last weekend’s race. So I leave the stile running on my own. Whilst racing I have now mastered the need to look behind to see how close the following runners are. I simply now focus on what I am doing, not on what others are doing. Remember you can’t control what they do! I am running on my own, monitoring the level of race focus energy (mental effort) I am using, checking that I am not using it up too quickly for a 3 hour 40 minute duration race. I guess after around 10 minutes of running I am rapidly joined by another runner. I couldn’t feel that there was anyone close behind, so it was a bit of shock when he seemed to rapidly join me. We run along with him directly behind me for a few minutes, and then he starts chatting. Now, there are times when to chat, and times when not to chat. Typically one chats in a race, when the intensity is down a bit, so therefore race focus energy isn’t in high demand to maintain the solid running pace. We were moving along at quite a rapid pace for a start of a marathon, especially when most people like to run conservatively at the start. So this wasn’t really the chatting time. So I reply with one word answers. The following runner continues to chat as I slightly up the intensity. I weigh up the options. Is he finding the pace really easy, or hopefully more likely, it is that he is adopting the strategy that I sometimes use in a race when I sense that the other runner is possibly stronger than me. This strategy involves trying to create the illusion that I am finding the pace really easy, like a training pace, no focus needed, hence able to chat away freely. I decide on the latter and experience an immediate swing down of the RPE – RFE arrow as my confidence grows as I conclude that he is concerned about my capabilities and he likely perceives himself as the weaker of the two of us. He asks where I am from, I reply from Brighton, which he comments “Your accent doesn’t sound like it’s from Brighton”. I decide that here is the golden opportunity to ‘throw a killer punch’! I therefore respond with a comment like “I can’t call myself a Kiwi anymore now that I race for the Great Britain elite trail running team!” He asks for further explanation, so I eagerly tell him about my racing at the World Champs earlier in the year in Connemara, Ireland. I then ask for his credentials. His name is Vince Kamp and his reply is that he is just getting into trail marathon running, although successfully winning the previous months Endurancelife Coastal Trail Marathon in Gower. He then concludes that he is a novice, and even comments out loud “Maybe I am going a bit too hard. I shouldn’t be running up here at the front with you, a GB International runner”. And at that instant, even with more than 24 miles of running to go, the winner of the race was pretty well determined, barring injury/cramp, or getting lost.

We run together for I guess another 15 – 20 minutes. I test him out on a few occasions by slowly/subtly increasing the intensity for a minute or two, just to try to get him to reconfirm his belief that I am much stronger that him. We then have a long descent where for the first time he runs to the front. Shortly after this descent we start climbing a steepish hill. To my surprise, he starts walking, even though the hill wasn’t a ‘walking’ hill, well not at this early stage of the marathon. I continue to run, and slowly overtake him. As I hadn’t put in an attack to drop Vince, I decide to simply keep the intensity constant, rather than up it. The last thing you want to do is to give the other runner a confidence boost by them seeing you significantly increase the pace to attempt to drop them, and for them to counter this attack and to reattach to you. So I am waiting for him to rejoin me, he doesn’t, so after a few minutes more of ‘waiting’, I then decide that now is the appropriate time to significantly increase the intensity for the next 10 – 15 minutes or so, in order to establish a larger gap.

As I don’t look behind while racing, there are only brief instances, as the course sharply turns, when I actually get an approximation on just how far behind he is. It isn’t until shortly after the turnaround point when we cross paths that the size of the gap is more accurately confirmed. I usually note the exact time it takes me to meet the following runner when on an out and back section of the course. On this occasion, probably as a result of the conversation we had had earlier, I didn’t feel the need to check the time gap. However, I did make sure that as we got close to each other and passed each other, I made sure that I looked as if I was just out for a cruisey Sunday training run. Chatting to Vince after the race, this was one thing he highlighted. Upon seeing me cruise past just after the turnaround point, he comments that it simply confirmed that I was in a “different league” to him. Remember the latest research on endurance fatigue mentioned in previous blog posts, based on muscle activation from the brain. Well self expectations play a large role in determining the amount of motor output/muscle activation. His self expectations therefore allowed him to accept me running away from him, and for his running pace to decrease. When I further questioned Vince about why he thought I was clearly going to beat him. It appeared that his reasoning was based on his assessment of his physical preparation. He hadn’t been doing as many miles training as he would want to, being significantly less than the mileage that he used to do in the past, and with him not realising that probably the most important benefit from physical training is actually the confidence it develops, it appears that he allowed this decrease in his physical training to lower his confidence levels.

The remaining 12 miles are back into a head wind. With around 7 miles to go I join into the half marathon field. The last time I experienced this was back in March in the Endurancelife Sussex Coastal Trail marathon. I recall during that race, that joining the half-marathon field really interrupted my race focus, and I significantly slowed. Having reflected on how I ran back in March, I had extensively prepared for this moment within my visualisations. I therefore managed to maintain a good pace last weekend, and slowly worked my way through the half marathon field. On this occasion I therefore used the half marathon runners as a positive, to swing the RPE - RFE arrow downwards as I passed each additional runner. Take a look at my Sussex marathon race report back in March, where on that occasion, joining the half marathon race caused an upward swing of the RPE - RFE arrow. Yes the importance of race reflection. The benefits of writing this blog!

Before I know it I am making my way up the last tough muddy climb with less than a mile to go, and shortly afterwards dib my dibber at the finish line in a time of 3 hours 47 minutes and 54 seconds. I am rather pleased with my performance, in terms of maintaining a pretty constant level of RFE usage throughout the entire duration of the race. The following link shows the data on the GarminConnect website: http://connect.garmin.com/activity/132621869, The graph below illustrates only a slight dropping of my heart rate. Even though, one would expect an increase in heart rate during an endurance event as a result of cardiac drift, (a rise in heart rate occurs when maintaining a constant running pace). During an endurance event, the amount of race focus energy required to maintain the same running pace increases as the race progresses. Therefore in order to maintain constant RFE usage, one’s running pace has to decline, and hence the slight decline in heart rate as the drop in running pace is more than the rise in heart rate due to cardiac drift.

Just a slight detour back to my negative split pacing strategy ‘rant’ earlier. In order to achieve a negative time split, actually requires quite a massive disproportional balance in terms of race focus, i.e. mental effort. To run at a constant running pace throughout a marathon actually means at the start, and for the early few miles the pace just typically feels so easy. However, to maintain that same pace near the end of the race requires massively higher levels of RFE, mental effort whatever you want to call it. This uneven distribution of RFE is in my view a totally flawed concept! It is RFE that needs to be constant during a marathon, not running minute mile pace, or even heart rate! The only exception is if you are one of the best of the elite. Remember though they the very top elite are a totally different ‘breed’ of runner. It seems strange that in terms of what elite runners are able to achieve, in no other way do ‘middle of the pack’ runners try to replicate what they do. They don’t try to run at 4:45 minute mile pace. They don’t try to train 150 - 200 miles per week. They don’t try to do 20 mile tempo runs. They don’t live and train at altitude. So why is it that many people have the idea that a middle of the pack runner can run at a constant pace throughout a marathon, or even produce a negative split, just because the best elite runners can achieve it!

Vince Kamp finishes in second place twelve minutes behind me, and wins the ‘smack down’ (MarathonTalk terminology) with Martin Yelling, as Martin finishes in a time of 4 hours 27 minutes. Click this link to listen to a three minute snippet from this week’s MarathonTalk podcast where Martin retells his experiences at the Endurancelife Dorset Coastal Trail Marathon. or click here to listen to the entire podcast. Third finisher in the marathon was Nick Wright in 4 hours 15 minutes. The first three women marathon finishers were really close: Jay Hairsine 5:04, Candice Mcdonald 5:05 and Alice Constance 5:06. For the remainder of the afternoon, around 800 runners in total cross the finish line, at the end of either; a 10km, half marathon, marathon or 34 mile ultra trail race. All finishers appear to be on a real ‘high’ experiencing a huge sense of achievement, having completed such a demanding but extremely scenic course. Take a look at a short video of the race to get a feel of the day on the following link: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U-UOP1zJDs4&list=UUqUCO1VyUz2wgNpHTZH0AmA&feature=plcp

There is a great atmosphere within the large hall at the finish line, as I start my second marathon effort of the day, i.e. non-stop talking for a few hours. Late in the afternoon I take a short break, and then at around 6:30pm, I kick off the first of the Live More Lecture Series for the season with a 40 minute talk titled “The Ultra Trail Mont Blanc: A Tale of Two Races – Preparation, Positivity, Performance”. The 40 minutes absolutely ‘flies by’ and I manage to get through most of my planned material, although unfortunately wasn’t able to fully explain my RFE Fatigue Model, which I introduce to the audience of around 70 runners during the 15 minutes of questions. The audience seem to take on board my ‘out of the box’ ideas, with the only heckling I receive being from my two sons, who were quite amazed that there were so many runners who actually paid money to hear me talk! There are then two really interesting talk by Tobias Mews and Phil Davis on The Marathon Des Sables, and by Andrew Barker, from Endurancelife, on the Norseman Xtreme Triathlon in Norway

So to summarise it was a really enjoyable day. From running strong during the marathon, to meeting loads of other runners, then to cap it off, for my presentation to be so well received. Thanks to Endurancelife for all their efforts in putting on such a great event. Thanks to all of the other runners for sharing such a challenging and enjoyable race.

To finish off this post, two signing off quotes which add a little bit more to some of the concepts I have raised above:

Lorraine Moller’s book is probably the best running book I have read, even better than Ryan Hall’s “Running with Joy”, Harvest House Publishers, 2011, and Charlie Spedding’s “From Last to First”, CS Books, 2009. Both Ryan’s and Charlie’s books are excellent, so probably a good time to mention/hint to your partner/family when they are searching for ideas for Christmas presents. (I doubt you will find Lorraine Moller’s book available in the UK, but could be available to order on the web somewhere!)

Well if you managed to get to the finish line of this blog post then you truly do have endurance abilities. So you just need to work on that self-belief! All the best with your TOTAL preparations.

Stuart

PS Don’t forget to check out MarathonTalk. Both Ryan Hall and Charlie Spedding have been interviewed by Martin and Tom, and both are excellent interviews.

If you have come to my blog for the first time to read my Endurancelife Dorset Coastal Trail Marathon race report, welcome, I hope you find your visit to my blog worthwhile. You will see from the length of my posts that they reflect the running that I do, i.e. marathon and ultra distance durations. So you will require reasonably high levels of endurance to manage to reach the end of each and every post!

One of the key benefits I get from writing my blog posts is that it provides quality time to reflect on my training and racing, in order to improve in subsequent races. I feel my performance in last weekend’s Dorset trail marathon, which I was pretty pleased with, was largely a consequence of the time I spent reflecting on my performance in my last race, the Beachy Head Marathon. It was in the process of analysing my performance in the Beachy Head Marathon, where I finished in 2nd place, but in a time 30 seconds slower than the year before, combined with the development of my Race Focus Energy Fatigue Model, where I identified what was required in order to produce a successful performance down in Dorset. With success being defined as a performance I am happy with, i.e. where I feel as if I have run as well as I can (yes, a rather vague criteria, which I will hopefully expand upon).

So as I prepared for the race, the key aim was to run hard and focused for the entire 26.6 miles (the distance advertised on the Endurancelife website and what my Garmin 305 watch indicated on the day). This desire to remain focused the entire way was in direct response to how I raced at the Beachy Head marathon, where I eased of the pace in order to unsuccessfully prepare for a tactical battle with the eventual winner. On reflection, easing off the pace between miles 19 – 23 resulted in me not able to feel totally satisfied with my performance. I guess if I had won the race I would have traded the easing off the pace, with the satisfaction of winning. Well that was the rationale I accepted, as I ‘gave in’ to the messages ‘bombarding’ me to slow down during the race.