Hi,

Yes, back again, and this time I promise that it will be

my last post to do with pacing for road marathons. I know that this UltraStu blog is meant to be about trail running, however, the underlying principles that I will try to explain for the last time here for road marathons do translate to the trails, but to a lesser extent, as there isn't the same 'obsession' with finish times when running on the trails.

Still Some Confusion Over the Likely Disappointment in Adopting an Even Paced Strategy

Why bother writing one last comment about road marathon pacing you may ask. Well it is because the standard accepted pacing strategy for road marathons, i.e. an even paced strategy or a negative split strategy, is totally the wrong approach for marathon runners, unless you are one of the World's very best. And the fact that this coming weekend at the London Marathon, thousands of runners will experience disappointment at not achieving their target marathon finish time, and for many, not because they are not capable, but simply due to them following the totally wrong standard accepted pacing strategy for road marathons, with the false belief that they are capable of achieving an even split marathon!

As I stated in my marathon pacing calculator post last week, the topic of pacing tends to be vigorously discussed, and as expected, my post last week generated some quite animated responses. But rather than directly respond to the comments that have been made during the last week, (which varied from containing some worthy points, to others being totally misguided or confused), I will simply attempt to clarify the confusion that is still evident.

Typical Road Marathon Goals

Lets start with: What is the purpose of running a marathon? Well, simple really, the number one priority is to get to the finish line. Apart from something catastrophic happening, pretty well nearly everybody with modest levels of fitness can finish a marathon. However, it could take a long time, perhaps up to nine hours if one walked at around 3 miles per hour, i.e. 20 minute mile pace.

Although most runners have their number one aim to finish, I have yet to meet a marathon runner who hasn't started the marathon without a thought, a guess at the time they think they can achieve. Many runners will then convert this possible time idea into a target marathon finish time. To start with for novice marathon runners, the target finish time may be to break six hours, therefore involving a mixture of walking and running. And then the next target is often to break the five hour barrier, which requires significantly higher levels of running. The targets then get quicker, typically to break 4 hours 30 minutes, then the magical four hour mark. As the finish time gets quicker, the target finish goal barriers tend to get closer, with the next target finish times tending to be 3:45, 3:30, 3:15 and then the 'holy grail' the even more magical sub three hour barrier. Other finish times between three and four hours are often targeted such as 'good for age' race places for various marathons, e.g. London Marathon, or BM times, i.e. Boston Marathon qualifier times. Once the sub three hour barrier is accomplished, the targets tend to get very narrow, e.g. 2:55, 2:50, 2:45 (which is the UK Athletics Male Championship qualifier time, then 2:40, 2:35, and finally, only reserved for the very best of male club runners, the sub two hour thirty minute barrier.

So as you can see from the above paragraph, pretty well every runner starting a marathon will have either some vague idea of a time they think they might be able to achieve, or for most runners, they will have a target marathon finishing time that they would like to achieve. Hence why it is so important that these runners have some form of pacing strategy to help them achieve their target goal finishing time, and hence why I published last week a

marathon pacing calculator that will help them pace the marathon and thus help them achieve their target time.

My Marathon Journey

Before I spend a little bit of time explaining in a little bit more detail just why the marathon pacing calculator will dramatically increase the likelihood of the runner achieving their target finish time, I will briefly provide a background of my marathon journey. Although this section provides some context regarding the importance of different target finish time barriers, skipping this section won't affect your understanding of the marathon pace calculator and why the positive split pacing strategy is more successful.

I mentioned above that in terms of target marathon times, runners may progressively move down the marathon goal time barriers, from five hours, next four hours, then eventually three hours For me, at the age of seventeen, I set the target immediately at breaking three hours, and I was successful with 2:56:51 in April 1980. Yes, 34 years ago!

Breaking the Three Hour Barrier - 2:56:51 - April 1980 - Rotorua, NZ

Having achieved the sub three hour goal, I left marathons aside for a few year before returning in 1984, now as a twenty one year old, with the sub two hour thirty minutes barrier as the target finish time. I'm not sure what happened to the 2:45, or even the 2:50 and 2:40 target times, but as a youngster I was always in a rush to get things done! Did I achieve my goal time. No! Unfortunately I missed the 'super magical' sub 2:30 by a mere forty seconds.

Failing to Break the Two Hour Thirty Minute Barrier - 2:30:39 - June 1984 - Christchurch, NZ

Yes, those forty seconds were massively meaningful. It meant the difference between massive joy and massive disappointment. I was so disappointed at not achieving my goal that I moved not only away from marathon running, but running full stop, for the next eight years or so, and ventured into multisport (i.e. kayaking triathlons), road cycling, triathlon, and then Ironman triathlon. It was only when preparing for the Ironman that I returned to the road marathon in 1992.

So you can see from above, how in some ways road marathons are quite different to trail marathons or ultras. On the trails, the finish time isn't really that relevant as no two trails are the same. But on the road, every marathon should be 26.2 miles, and although road routes will vary a bit in terms of undulations and exposure to wind, on the whole, road marathons tend to be over reasonably flattish courses, so direct comparison of marathon times are possible. So the consequences of running just forty seconds, yes just forty seconds slower that I hoped for changed my entire endurance athlete experiences. For the better or for the worse, I don't know. But I do recall that at the time I was very disappointed. Bizarre really, considering it was such a quick time, especially for a twenty one year old. But as I have found, runners tend to be very 'hung up' about their race goals, and often will be very despondent over a time only slightly slower than their target time, even though in reality it is a great achievement. But that is just the nature of many runners!

Therefore being just a few minutes slower than target finish time, or even just a few seconds slower, isn't what one wants. The majority of runners want to achieve their target finish time for the marathon. Hopefully most people will agree with this statement!

So back to my marathon journey through the years. Yes, in 1992, I was a full-on Ironman triathlete. I had successfully qualified for the Hawaii Ironman at the end of the year, by finishing in 13th place overall at the very first 1992 Lanzarote Ironman, running the marathon portion of the Ironman in three hours and seven minutes. Wanting to perform to my best at Hawaii, I placed more emphasis on my road running and entered the Scottish Amateur Athletics Association Marathon Championship in August 1992, which were being held in Elgin, near the top of Scotland. I had been living in Aberdeen, Scotland for nearly a year, and so according to the AAA rules I was therefore eligible for the Championship, which was a pleasant surprise when I was awarded the bronze medal for finishing third in an official time of two hours thirty minutes, and this time sixteen seconds (2:30:16). Yes, the super magical sub 2:30 barrier was still beyond me. But now only by seventeen seconds, Yes a measly seventeen seconds!

Again Failing to Break the Two Hour Thirty Minute Barrier - 2:30:16 - August 1992 - Elgin, Scotland

For the next few years I continue with Ironmans, triathlons and then duathlons, and it was in 1995, in preparation for the prestigious Zofingen Powerman Duathlon consisting of 13km run, 150km bike, and 30km run, that I ran the 1995 London Marathon. And yes finally in April 1995, fifteen years to the month since I broke the sub three hour barrier, and eleven years after being so close (40 seconds), I finally manage to go sub two hours 30 minutes with 2:29:34!

Finally Breaking the Two Hour Thirty Minute Barrier - 2:29:34 - April 1995 - London

Yes finally, I had made it. Only by twenty six seconds, but those twenty six seconds were HUGE! Yes, I recall at the time that upon finishing I was a bit disappointed with my finish time, as I had been running really well and was expecting to finish up to five minutes quicker. But looking back now, whether I had run 2:28, 2:27 or even 2:25, these times in essence are all the same, simply sub 2:30. Yes, these barrier goal times are important, hence why just a few seconds either way can be so meaningful.

Having achieved my long term marathon goal, there wasn't really anything else to achieve marathon wise. I didn't believe I had what it took to be a sub 2:20 marathoner, so I again drifted away from the marathon. Then in 2003, now as a forty year old, the prospect of running a quick marathon as a 'veteran' was appealing. Unfortunately I didn't believe I could run sub 2:30 at the 'old' age of forty, so a 'soft' target time of sub 2:40 was my goal finish time. And as you would expect, achieving the soft time that I had set was pretty easy, although, I did make tough work of it due to the lowered expectations, so I ended up struggling to a finish time of 2:39:12.

Slowing Down But Breaking the Two Hour Forty Minute Barrier - 2:39:12 - April 2003 - London

Following 2003, I finally 'let go' of the stopwatch and headed to the trails. To date I have now raced thirty one trail marathons, and without the 'restriction' of the stopwatch, my running has gone from strength to strength. From those thirty one trail marathons, I have won nineteen of them, finished second on eight occasions, finished in fourth place once, fifth place twice, and finally my most recent trail marathon last month, a disappointing DNF!

My First Ever Trail Marathon Did Not Finish (DNF) - 00:00:00 - March 2014 - Steyning

Please note that I have made reference to some of my successes I have achieved with regards to marathon running, not to 'blow my own trumpet', a saying that my mother would always criticise people for, but I guess partly in response to a comment left on

last week's blog post that suggested that my performances have been "

hit and miss" and that I have performed poorly due to poor pacing strategies!

"To me your race success has been really hit and miss over the last few years. .... Personally I think a big part of the problem is your pacing strategy" Well I don't think in any of these thirty one marathon races (excluding the DNF due to injury) that I had a "

problem", as I didn't perform poorly. Sure, in some races I didn't achieve the 'perfect performance', but to try to discredit the positive split pacing strategy, by classifying my performances as poor, I find a bit bizarre. Especially with the criticism coming from a 3:30 marathoner who has "

nailed" all of his recent races!

"How do I know.... well in all of my races in the last 9 months- four races, three ultras and one marathon I nailed them all, in the only two race that I had done before I did big PB's."

So, as my personal marathon journey above illustrates, I have had quite a long association with the marathon. For the majority of my marathons, there has been joy and satisfaction, but intermingled in relation to road marathons, there has been disappointment, at times deep disappointment, which looking at it now seems rather pointless. What do a few seconds matter? Yes, I know to the 'outsider' a few seconds mean nothing, but to the road marathon runner, those few seconds can be very meaningful, and hence why with my marathon pace calculator, I am trying to help potentially thousands of marathon runners this weekend at London to avoid this disappointment of not achieving their target finish time, which may be missed by just a few seconds, and for many simply due to trying to adopt a a flawed even paced strategy! That is my motivation, and why I am hopefully not wasting my time, trying to clarify the confusion that exists out there! So please forward the following link to the Marathon Pace Calculator

website to people you know running at London on Sunday.

http://rsusmf.appspot.com/

The Marathon Pace Calculator

So lets look in detail at my marathon pace calculator. The calculator was based on the data of the first twenty five thousand finishers at last year's London Marathon. Yes, 25,000 runners finished before five hours and two minutes, so I did not include the data from runners slower than five hours and two minutes. The

blog post from May last year described the process in detail, but to summarise, I analysed the data of these 25,000 finishers in blocks of one thousand runners, except at the very top end of the field I analysed the data in blocks of one hundred runners. I looked at the number of runners per thousand or hundred block that ran an even or negative split, and then looked at the average percentage slowdown that occurred for each block of runners. It is this

average slowdown percentage that is used within the marathon pace calculator to calculate the percentage slowdown. Which is then used to give the most important information required by the marathon runner, being:

What pace should I go out at, should I run at during the first part of the marathon? And also,

what time should I aim to run through half way in?

Now if you follow the standard pacing advise that

an even paced marathon strategy is best, then the answers to these two key questions are easy. Simple,

your time at half way is simply half of your target marathon finish time, and the pace to start at, is the same pace you aim to run for every one of all of the twenty six miles, which is simply your target marathon finish time, divided by 26.2 miles. Straight forward really. No need for a marathon pace calculator. Simple!

UNFORTUNATELY IT IS NOT THAT SIMPLE. IF RUNNERS TAKE THIS EVEN SPLIT APPROACH THEN THEY HAVE A NINETY FIVE PERCENT LIKELIHOOD OF

NOT ACHIEVING THEIR TARGET MARATHON FINISH TIME. I will repeat, they have a 95% likelihood of NOT achieving their target marathon finish time!!! It is as simple as that! That is the data from the first 25,000 runners from last year's London Marathon.

Those of you may recall that last week I stated that they had a 96% likelihood of NOT achieving their target time, why now reduced to 95%. Well the 96% refers to the entire field of 35,000 runners, having just re-checked my data. When looking at only

the first 25,000 finishers, i.e. quicker than 5:02, it becomes 95%. Yes, only FIVE PERCENT, yes I will repeat! Only 5% of these runners managed to run an even paced or negative split run. That is they managed to run the second half of the marathon at the same pace or quicker that their first half of the marathon. Now bearing in mind, if the runner has adopted the even paced strategy, they will pass through half way in exactly half of their target marathon finish time. With 95% of the runners, running the second half of the marathon SLOWER, then this means that 95% of runners MUST THEREFORE NOT HAVE ACHIEVED THEIR TARGET MARATHON FINISH TIME!

Now I don't know how I can make this above point much clearer. It is not me mis-using the statistics as accused by Thomas in a comment left on the

linked blogpost "

I used to read Stu's blog a lot but eventually gave up, and it was his (mis?)usage of statistics that finally made me take him off my reading list." The above is the correct interpretation of the data from last year's London Marathon. If anyone is able to explain to me how I have got the above conclusion (T

hat 95% of runners MUST THEREFORE NOT HAVE ACHIEVED THEIR TARGET MARATHON FINISH TIME) wrong then please leave a comment. below on this post.

Some people may suggest that running a positive split strategy, i.e. running the first half of the marathon quicker than the second half of the marathon will result in the first half being run far too quickly, and the runner will 'blow up'! Now I don't want to get into a discussion here what 'blowing up' means, but if one simply looks at the data from the 2013 London Marathon, if runners don't adopt a positive split strategy then it is near guaranteed, well 95% certain, that they won't achieve their target finish time, as 95% of them will slow down during the second half of the marathon. Considering that the even paced strategy is so widely recommended in pretty well all publicity mediums, such as magazines and podcasts, then even with this being the standard pacing message, 95% of runners quicker than five hours are

still not managing to run an even paced marathon.

Now you may argue, that if the runner runs the first half of the marathon even quicker, then more runners will slow down during the second half of the marathon. And yes, that is exactly what should happen. Slowing down during the second half of the marathon is a reality, as demonstrated by the fact that 95% of the runners do slow down. It is quite simple really. Accept that slowing down during the second half of the marathon occurs, so take this slowing down into account when planning your pacing strategy, so one is still able to achieve their target marathon finishing time, even though they have slowed down. If runners plan their pacing strategy, wishing, hoping, expecting not to slow down, so hoping that they are the one in twenty runners that don't slow down, then yes, they have a one in twenty chance of achieving their target marathon finishing time. But odds of one in twenty don't sound too appealing to me!

The Under-Trained / Inexperienced / Foolish Argument

A frequent counter argument to the presentation of this very low percentage of runners that are actually able to run a marathon with an even split between their first and second half marathon split times, is that just because this is what occurs it doesn't mean that this is the best or the most efficient strategy. Comments like the following are often left:

"How many runners are under-trained for the marathon, yet you happily include their stats? How many runners make *obvious* pacing or executional mistakes, yet you include their stats too?"

"Huge numbers of people running a big city marathon are inexperienced, and you can put money on them going off too quickly. Foolish, but predictably foolish."

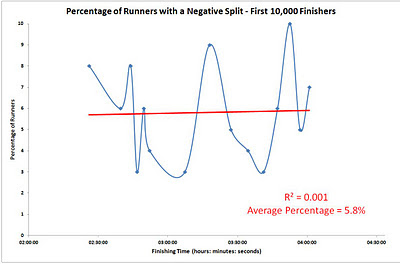

So lets maybe restrict the data analysis to the

first 11,000 runners that ran quicker than four hours. Yes, there are more runners that do achieve an even paced or negative split, but this percentage is only

increased up to eight percent for the quicker runners able to finish under four hours. So even with the percentage of quicker runners being able to run an even split strategy only increasing up to 8%, there is still a massive 92% likelihood of failing to achieve the target marathon finishing time. So to conclude; Adopting a pacing strategy that only has an eight percent (8%) likelihood of succeeding doesn't really seem to be the "best or most efficient" strategy. Rather it seems a pretty poor strategy to adopt!

Okay maybe these sub four hour runners are simply under-trained, inexperienced and foolish. So simple, lets move to the very top end of the massed start field. So we are ignoring the elite start, as remember what the elite are able to achieve has absolutely no relevance to the non-elite runners. (Note: Please refer to the bottom of this post for an explanation into why what elite marathon runners are able to achieve is not relevant to the non-elite runners.) So if we look in detail at the

first one hundred massed start finishers, so those runners that finished

quicker than 2:36:53, then surely these runners would obviously demonstrate the even paced / negative split pacing strategy works. What would you expect from these very best non-elite runners, maybe 80% of them achieving an even paced / negative split pacing strategy? Or maybe these very best runners, which one surely couldn't argue as being under-trained, inexperienced or foolish, that maybe 90% of them would achieve an even paced / negative split pacing strategy, thus finally providing indisputable evidence that the even paced / negative split pacing strategy is the best, the most efficient pacing strategy.

So what percentage of these very best non-elite, well-trained, experienced and not foolish runners achieve an even paced / negative split pacing strategy? The ANSWER, JUST ONE RUNNER. I will repeat, yes JUST ONE RUNNER, therefore just ONE PERCENT of the very best non-elite runners achieved an even paced / negative split pacing strategy! Does anyone really need any further evidence that running an even paced / negative split pacing strategy is NOT the sensible strategy to adopt. Now if anyone is able to provide a counter argument to this amazingly clearly obvious data, then please leave a comment below.

How Much Slow Down During the Second Half of the Marathon?

So hopefully everyone should now fully understand and accept that adopting an even paced / negative split pacing strategy is reducing the likelihood of achieving ones target marathon finish time. The

very best non-elite road marathon runners, who are likely to be the best trained, the most experienced non-elite road marathon runners,

DON'T DO IT, so why should other lesser trained, lesser experienced runners try to adopt an even paced / negative split pacing strategy?

So the immediate question that arises is then just

how much should the marathon runner expect to slow down during the second half of the marathon? This is where the marathon pacing calculator is so useful. Yes, this is why I am spending time typing out this blog post, so potentially thousands of runners this coming Sunday are not disappointed, as they will therefore have some guidance on what pace to start out at, and what time they should pass through the half marathon mark.

As mentioned above, the marathon pace calculator uses the average percentage slowdown based on the data from the first 11,000 finishers, i.e. all runners that finish under four hours. And the percentage slowdown used within the marathon pace formula varies for different finish times, with the very quickest runners, i.e. runners targeting a marathon finish time of sub 2:37 using a 5.06% slowdown, increasing for runners targeting a finish time slower than 3:17 using a 9.92% slowdown.

Now some people argue that adopting a positive split strategy, i.e. slowing down during the second half of the marathon can be "

psychological demoralizing, as (the runner) is being passed by runners who are looking stronger and fresher". However, the marathon pace calculator

uses the average percentage slowdown, so if the runner completes the second half marathon with the exact percentage slowdown used within the marathon pacing formula, then they will overtake an equivalent number of runners during the second half of the marathon, equivalent to the number of runners that will overtake them during the second half of the marathon. Which although slowing down and running the second half of the marathon slower, their actual race position will stay the same if the runner runs at the exact percentage slowdown used within the marathon pace calculator.

By adopting the marathon pace calculator average percentage slowdown pacing strategy,

the running pace up to the half way point in the marathon will be quicker than if adopted the flawed even pace strategy. How much quicker will this pace be? Well the amount the pace is quicker is dependent upon the target marathon finishing time, as not only does the percentage slowdown vary dependent upon the finish time, but because the slowdown is expressed as a percentage, having a slower target finish time actually results in the runner slowing down more minutes during the second half. So slower finish time runners will have to run at a quicker pace, to gain more minutes quicker during the first half of the marathon, in comparison to the even paced strategy runner. Faster finish time runners don't have to gain as many minutes by running quicker during the first half. The idea of having to run so many minutes faster during the first of the marathon may sound a bit daunting. But remember if you decide to run the first half of the marathon at the slower, even paced strategy running pace, then sure it will feel easier to half way, but this isn't much good, as you only have a one in twenty chance of achieving your target finishing time! So lets look at some specific examples.

The Sub Four Hour Marathoner

Running a sub four hour marathon adopting an even paced strategy requires

a minute mile pace for every one of the 26 miles to be run at 9:09. The runner would pass through half way in

1:59:59.

Using the

ReSUltS marathon pace calculator which incorporates a 9.92% slowdown during the second half of the marathon.

For the first 13 miles of the marathon, the calculator requires a 8:43 minute mile pace. The runner would pass through half way in

1:54:19, which would be five minutes and forty seconds quicker, yes 5:40 quicker. What is the likely impact of running 5:40 quicker to half way? Well if running 5:40 quicker to half way results in the runner setting a half marathon personal best time, then there is obviously something wrong. Not that the ReSUltS marathon pace calculator is wrong! No, the runners target finish time is obviously too quick. And in this instance, no matter what pacing strategy the runner adopted, it is most probable that they would not achieve their target finish time. Target marathon finish times must be realistic and based on some evidence / data, rather than just 'guessing' a time. But generating target marathon finish times is a totally different topic. What the ReSUltS marathon pace calculator assumes is that the target marathon finish time is realistic.

So for the sub four hour target marathoner, the runner would pass through half way in

1:54:19, which would be five minutes and forty seconds quicker, yes 5:40 quicker. However, for every mile after the half way point, the even paced strategy runner must maintain the same 9:09 minute mile pace, even though they will start to fatigue, which every marathon runner will tell you occurs! Whereas the runner that has adopted the positive split strategy, using the pacing plan proposed by the ReSUltS marathon pace calculator, for

every mile after half way they are allowed to gradually slow down, as the fatigue gradually builds up. One doesn't get to the half way point in a marathon and instantly become fatigued! No, the fatigue builds up gradually. So to mimic this gradual build-up of fatigue during the second half of the marathon, the required minute mile pace to achieve the target finishing time gradually gets slower. So for those really challenging last six miles of the marathon, the positive split strategy runner is able to run the last six miles at the pace of: 9:41, 9:48, 9:55, 10:02, 10:09, 10:17. Yes, they are able to slow down to a minute mile pace of 10:17 and still achieve their target finish time. Doesn't that sound more realistic than the even paced strategy runner, still trying to run a 9:09 minute mile, the same pace they ran at the start when totally fresh, now nearly four hours later when absolutely exhausted from running 25 previous miles.

Yes, I know that the runner is highly unlikely to run exactly to the minute mile pace times provided by the ReSUltS marathon pace calculator. Whether they slowdown at the same rate that the calculator forecasts, or at a quicker rate, but they don't start fatiguing until say mile 18, it isn't really important. What is important is that the runner is able to slow down and still achieve their target finishing time. What is important is that the runner accepts that slowing down during the second half of the marathon is a reality, and therefore must plan for it! To 'dream', to 'wish' that they won't slow down, and therefore not plan for any slowing down, even though the very best non-elite marathon runners slow down during the second half, is just total foolishness!

The Sub Three Hour Marathoner

Running a sub three hour marathon adopting an even paced strategy requires

a minute mile pace for every one of the 26 miles to be run at 6:52. The runner would pass through half way in

1:29:59.

Using the

ReSUltS marathon pace calculator which incorporates a 6.57% slowdown during the second half of the marathon.

For the first 13 miles of the marathon requires a 6:39 minute mile pace. The runner would pass through half way in

1:27:07, which would be two minutes and fifty two seconds quicker, yes 2:52 quicker. Okay it is 2:52 quicker than the even paced strategy at half way, but this isn't massively quicker, which many people seem to misinterpret from the idea of adopting a positive split strategy. Many people seem to interpret the positive split pacing strategy as 'going out at suicide pace'. As you can see from this sub three hour marathon target example, getting to the half way point 2:52 quicker, yes, requiring more effort and focus, but I don't think it could be classified as being ridiculously faster!

However, for every mile after the half way point, the even paced strategy runner must maintain the same 6:52 minute mile pace, even though they will start to fatigue, which every marathon runner will tell you occurs! Whereas the runner that has adopted the positive split strategy, using the pacing plan proposed by the ReSUltS marathon pace calculator, for every mile after half way they are allowed to gradually slow down, as the fatigue gradually builds up. And for those really challenging last six miles of the marathon, the positive split strategy runner is able to run the last six miles at the pace of: 7:08, 7:12, 7:16, 7:20, 7:24, 7:30. Yes, they are able to slow down to a minute mile pace of 7:30 and still achieve their target finish time. Doesn't that sound more realistic than the even paced strategy runner, still trying to run a 6:52 minute mile, the same pace they ran at the start when totally fresh, now nearly three hours later when absolutely exhausted from running 25 previous miles.

Hopefully, the above two examples have helped illustrate how the

ReSUltS marathon pace calculator works, and it is provides guidance on a pacing strategy that represents what is a reality, the marathon runner getting fatigued as they progress through the marathon. Now I haven't ever met a marathon runner that didn't fatigue as they ran the marathon to the best of their ability. Fatigue occurs, it is a reality, no argument! So surely as one fatigues then one should expect to start to slow down. Surely this must now make sense!

As usual my short blog post has ended up near ultra length. Sorry about going on and on, and no doubt repeating myself above many times. Hopefully my more detailed and lengthy explanation of how the

ReSUltS marathon pace calculator works, has helped to clarify why the positive split pacing strategy is clearly the strategy to adopt to maximise the likelihood of achieving ones target marathon finishing time!

Please spread the word on the

ReSUltS marathon pace calculator, and how it takes the guess work out of deciding how much one should expect to slow down during the second half of the marathon. And to those of you after reading all of the above, that

still think that you should NOT expect to slow down during the second half of the marathon, I am sorry but I am unable to help you.

Signing Off

I will sign off with a quote that I have signed off with previously when discussing the foolishness of the negative split pacing strategy. The quote is from Tom Williams, one of the hosts of the excellent

MarathonTalk podcast. Yes, I am an avid listener of MarathonTalk and have been for the last three or so years. Pretty well all of their advice on the show is sound quality advice, which assists thousands of runners to achieve their running goals, EXCEPT ONE, their celebration of the negative split. For some unknown reason, they are just totally off the mark here!

It just so happened that last Sunday, Tom Williams ran the Greater Manchester Marathon and crossed the finish line in an excellent 104th place overall, with an official chip time of 2:53:04. Did Tom, a massive supporter of the negative split, achieve a negative split in running 2:53:04. Yes, indeed he did! Using his chip time, he ran the first half marathon in 1:27:04, and then ran the second half marathon in 1:26:00. So a negative split of 64 seconds! Fantastic! That is, if you believe that the negative split is the sign of a well run marathon. And with MarathonTalk taking this view, no doubt there will be huge celebrations on MarathonTalk this week!

However, how did Tom manage to achieve this 64 second negative split? Simple really, by running the first half marathon so slowly, which although he ran the second half marathon 64 seconds quicker, his overall finish time is quite a bit slower, (possibly up to four minutes slower), than the marathon time that one would expect that he should be able to achieve, based upon his recent 10 mile road race time of 60:54. A ten mile road race finish time of 60:54 should definitely correspond to a quicker marathon time than 2:53:04. How much quicker is debatable, and one could look at various marathon predictor websites, which produce a range of predicted marathon times from 2:49:03 to 2:51:19. The precise likely marathon finish time isn't really that important. The important 'take home' message is that Tom only managed to achieve a negative split by running slower than his true current marathon potential.

Listening to Tom on MarathonTalk, I know that he publicly stated that he wasn't going to race the Manchester Marathon to the best of his ability. Yes, this is fine. But hopefully Tom and his co host Martin will not massively celebrate his negative split achievement, as the negative split has only been achieved due to not running as quickly as he could. And celebrating the negative split pacing strategy, will encourage the thousands of MarathonTalk listeners to adopt the totally wrong pacing strategy, if they wish to maximise their chances of achieving their target marathon finish time.

(Please Note: I have just listened to the first portion of this week's MarathonTalk episode, and I would just like to congratulate Tom and Martin for not celebrating Tom's negative split. No doubt with Tom in the past being such a supporter of the negative split, that it must have been so tempting to massively celebrate his negative split achievement. Maybe Tom has changed his views since 2011, and now 'has his money on' the positive split. Now accepting that the negative split is only achieved by running the first half of the marathon slower than ones ideal pace. Anyway I just wanted to thank Martin and Tom for not encouraging their thousands of listeners to adopt a negative split pacing strategy for London Marathon. Stuart - 10th April, 2014)

So finally here is Tom's sign off quote from 2011. And Tom, if you are reading this, please leave a comment below, letting us know what your 2014 views are on the ideal marathon pacing strategy.

“My money's still on the even / negative split but I'd be delighted to be proved wrong. My quote for the day... I'd rather know I was wrong than think I was right ;)" Tom Williams, 2011.

All the best to everyone running this Sunday's London Marathon.

Stuart

PS

The Elite Marathoner World Record Argument

The following is a small section on why what elite marathon runners are able to achieve is not relevant to the non-elite runners. Because as always when it comes to justifying the even paced / negative split pacing strategy argument, this is the one argument that is also provided, and as expected was included in comments that were left last week.

From Brett: "

The point I was trying to make was to look at all the current records in distance running - if they all are even to slightly negative splits, that has to mean something. For example, the current marathon world record is around 2:03 and was an even split to nearly the second."

"

In the USA, we also had the 100 mile track record broken a couple times in the last few months. The first time it was broken (Jon Olsen), he ran two 50 mile splits within 2 minutes of each other. The latest time the record was broken a few weeks ago (Zach Bitter), he ran a slight negative split of a few minutes in the second 50 mile section. So as best I can tell, this same behavior is seen across ultramarathons and down to half marathons and 10ks as well."

In case you haven't seen my reply to these World record arguments, I will simply paste the comment I left in response to Brett's World's best approach below.

"

When in any other situation does the club level athlete, the 'average' person (although I dislike the word average but I think it makes the point clear) try to mimic what the World's best can do. Whatever activity; e.g. scoring a maximum 147 break in snooker, cycle racing at top-end pace for hours every day for near 22 consecutive days around and over the alps of France, or managing to descend to an ocean depth of 214 metres on one single breath. Yes, regardless of the activity, 'average' people do not expect to be able to replicate these amazing feats. So please explain to me, why is it that when it comes to running road marathons, that it is assumed that the 'average' person, who is not a full-time athlete, who does not have the same opportunities to prepare, the same resources, the same environment, and dare I say, the same genes, that this 'average' person can then achieve the same as the World's best, I just don't understand! Could someone please explain this logic." Stuart Mills, last week.

The most important thing to remember is that you, me, and pretty well every other reader of this blog post are not the World's elite, so what the World elite do is not relevant. How the World elite manage to achieve what they do I just don't know, and to be honest, neither do the sports scientists really know. What they can achieve is at times just unbelievable, e.g. often 'throwing' in a mega super quick 5km split shortly after halfway in a marathon. But the key thing to take away from what these World elite do, is that they are so different to you and me, that it isn't worth trying to work out how they do it. Trying to compare myself to them is just total foolishness, although some people do seem to want to do this when it does come to both running an even paced race or even better a negative split. Yes, it is good for the ego to compare that you achieve the same pacing strategy as the World elite, but the fact that one is only able to achieve an even paced or negative split pacing strategy by running the first half of the race so slowly is just 'ego massaging'. Many people can run the last mile or quarter mile of a marathon quickly if they run earlier portions of the race slowly. The aim is to run the entire 26 miles as fast as possible not just the last mile!